The internally displaced persons (IDP) crisis in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) remains one of the world’s most complex humanitarian emergencies, driven by decades of armed conflict, resource competition, and regional instability. This piece examines the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) and its operational strategies, specifically the deployment of rapid reaction forces, community engagement initiatives, and resource allocations, alongside the external factors that have influenced its effectiveness.

Using Liberal Institutionalism as a theoretical lens and a qualitative, triangulated methodology, the publication finds that MONUSCO’s rapid reaction forces have provided short-term security gains but have struggled to achieve sustainable reductions in displacement. Community engagement has fostered trust and improved humanitarian coordination, yet faces cultural and logistical barriers. Resource constraints and disproportionate military spending limit broader humanitarian impact. External pressures, including regional conflicts, fluctuating international policies, and local political dynamics, further constrain outcomes.

The findings offer actionable lessons for future peacekeeping missions: align military and humanitarian priorities, invest in local capacity building, and ensure mandates are adaptable to complex, multi-actor conflict environments.

Eastern DRC’s Displacement Epicenters, Peacekeeping Mandate, and Escalating Risk

The eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), principally North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri, have long been recognized as the country’s displacement epicenter and one of the most enduring humanitarian crises globally. These provinces embody a complex nexus of violence, displacement, and resource exploitation that has persisted for decades. Armed groups compete not only over territory but also over access to lucrative mineral economies and taxation routes, entrenching cycles of violence that continually uproot civilian populations. Weak state institutions, porous borders, and the entanglement of regional actors in Congo’s conflicts have compounded this instability, producing what observers increasingly describe as a “permanent emergency” (Vlassenroot, 2008; Vogel & Musamba, 2017).

Historically, the displacement crisis is rooted in the upheavals of the 1990s, including the First and Second Congo Wars, the influx of refugees after the 1994 Genocide perpetrated against Tutsis, and the proliferation of non-state armed actors who entrenched themselves in eastern DRC’s social and economic fabric. Over time, displacement has shifted from being episodic and linked to specific outbreaks of violence to becoming chronic, protracted, and multi-generational. The persistence of conflict and the absence of durable political settlements have created conditions where families are displaced multiple times within their lifetimes, often oscillating between camps, informal settlements, and fragile host communities (Coghlan et al., 2007).

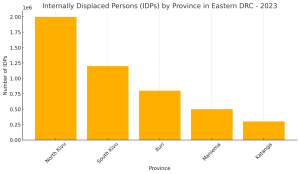

The scale of the crisis today is staggering. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), by October 2023, the DRC hosted a record 6.9 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), with 5.6 million concentrated in the eastern provinces alone, the highest figures ever recorded in the country’s history. These numbers were driven primarily by renewed offensives from the March 23 Movement (M23) and other armed groups. Subsequent humanitarian situation reports from OCHA and ReliefWeb in 2025 indicate further mass movements, with displacement surging around the city of Goma as fighting expanded into peri-urban zones (IOM, 2023; OCHA, 2025). Before this escalation, the country already hosted 6.7 million IDPs, suggesting that new waves of displacement are compounding rather than replacing existing humanitarian burdens. Such trends underline the cumulative and structural nature of displacement in eastern DRC: far from being a temporary by-product of conflict, it has become a defining feature of everyday civilian existence.

Amid this humanitarian catastrophe, the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) has served as the principal international mechanism tasked with protecting civilians and stabilizing conflict-affected zones. Established in 2010 as the successor to MONUC, MONUSCO has been the UN’s largest peacekeeping operation, at times deploying nearly 20,000 uniformed personnel. Its mandate has consistently prioritized the protection of civilians, with specific reference to IDPs as among the most vulnerable groups. UN Security Council Resolution 2502 (2019) explicitly re-emphasized the mission’s civilian-protection duties, mandating it to: (a) deter and respond to imminent threats of violence against civilians, (b) monitor and report human rights abuses, including those against displaced populations, and (c) advocate for durable solutions such as safe, voluntary returns or dignified integration into host communities.

In practice, this mandate has translated into a range of operational strategies. Proactive patrolling of conflict-affected territories has sought to deter armed group activity, while rapid reaction forces have been deployed to respond to imminent threats against IDP camps and settlements. MONUSCO has also acted as a facilitator of humanitarian access, securing corridors for aid delivery in volatile zones where NGOs and humanitarian agencies face high risk. Moreover, its presence has carried symbolic weight: in displacement-affected communities, the “blue helmets” have often represented the only semblance of international concern for populations otherwise abandoned by state institutions.

Yet, as my IR Graduate Program thesis highlighted, these interventions have been uneven and often constrained by broader structural dynamics. The geographic scale of eastern DRC, the multiplicity of armed actors, and the chronic underfunding of humanitarian responses have meant that MONUSCO’s protection efforts, while impactful in specific localities, have rarely translated into sustainable or systemic security gains. Furthermore, as the mission undergoes a phased drawdown, with withdrawal from South Kivu completed in June 2024 and its mandate extended only exceptionally until December 2025, the question of who will protect IDPs in the absence of MONUSCO looms large. Without robust transition strategies, including the empowerment of Congolese security institutions and stronger humanitarian coordination, the risks of escalating displacement and heightened civilian vulnerability remain acute.

Grounded Testimony & Qualitative Texture

On the ground, testimonies from humanitarian actors highlight the acute scale and severity of displacement in eastern DRC, where conditions in camps often mirror the violence and deprivation that forced people to flee in the first place. In Bulengo camp near Goma, medical staff reported receiving five to seven survivors of sexual violence every day, with an alarming increase in cases involving children, an indicator of how overcrowding, insecurity, and overstretched humanitarian services amplify exposure to exploitation and abuse. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) documented a surge in caseloads of sexual violence survivors in and around Goma into the tens of thousands between 2023 and 2025, while simultaneously managing outbreaks of cholera, malnutrition, and untreated trauma, illustrating how displacement deepens both physical and psychosocial vulnerabilities. These realities are not isolated: the Norwegian Refugee Council’s (NRC) February 2025 field updates describe families repeatedly uprooted and left “with no safe place to go,” as camps themselves became unsafe due to armed incursions, looting, and deteriorating humanitarian access. Together, these accounts complicate the perception of camps as neutral havens, underscoring that displacement in eastern DRC is not only a humanitarian crisis of numbers but also one of dignity, bodily integrity, and protracted insecurity.

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) by province in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in 2023, with North Kivu hosting the highest displacement burden. Graph generated by the author, using data adapted from UNHCR & Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), 2023.

MONUSCO’s Security Toolkit and Its Limits

MONUSCO’s operational repertoire in eastern DRC has combined traditional peacekeeping strategies with more robust security mechanisms. Chief among these were the Rapid Reaction Forces (RRFs) and the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB), designed to deter raids on IDP sites, reopen humanitarian corridors, and stabilize conflict zones in North Kivu and Ituri. Between 2018 and 2021, internal reporting suggested that RRF and FIB units thwarted more than 70 attacks on civilians and displacement camps in North Kivu alone, contributing to short-term reductions in violence and localized improvements in humanitarian access. Communities in areas with visible RRF presence frequently reported increased trust in peacekeepers and greater confidence in traveling to markets, schools, or agricultural fields, highlighting the immediate “protection dividend” of MONUSCO’s kinetic interventions. This resonates with broader research on UN peacekeeping as a form of “protection through presence” (Fjelde, Hultman & Nilsson, 2019), whereby the symbolic and deterrent value of international troops contributes to civilian security beyond the actual number of armed engagements.

Yet again, my IR Graduate Program thesis demonstrated, these gains have consistently eroded once units redeployed or mandates shifted. The persistence of structural drivers, elite predation, regional interference, and the resource-taxation economies of armed groups has meant that even successful deterrence in the short term failed to consolidate long-term civilian protection. This dynamic reflects a central tension within Liberal Institutionalism. The theory assumes that institutions like MONUSCO can shape behavior, establish norms, and reduce the transaction costs of cooperation; however, it also acknowledges that institutions are embedded in power asymmetries and cannot substitute for the political will of sovereign states or regional actors (Ikenberry, 2020; Johnson & Heiss, 2023).

In eastern DRC, MONUSCO’s capacity to enforce protection was always contingent on both host-state consent and the fluctuating political calculus of neighboring governments, particularly Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda. The mission could deter attacks in the short run but lacked the structural leverage to dismantle cross-border support networks or reform the Congolese state apparatus that often perpetuated cycles of displacement.

In institutionalist terms, MONUSCO illustrates the limits of what Keohane (1984) termed “institutionalized cooperation.” The mission created platforms for coordination between humanitarian agencies, the Congolese government, and civil society. It reinforced global norms around the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) by actively patrolling IDP camps and securing humanitarian corridors. However, the asymmetry between norms and enforcement mechanisms became stark: while the mission embodied the liberal belief in cooperative institutions, its dependence on troop-contributing countries, the Security Council’s shifting political will, and Congolese government consent constrained its effectiveness. Thus, MONUSCO both validates the liberal institutionalist claim that multilateral institutions matter in shaping behavior and simultaneously exposes the fragility of institutional responses in contexts of contested sovereignty and geopolitical rivalry.

The Drawdown, Reassessed From South Kivu Exit to 2025 Extension

This tension is especially visible in the drawdown process. On 30 June 2024, MONUSCO formally ended its presence in South Kivu, closing its Bukavu office after more than two decades. This was framed as a milestone in the Congolese state’s path to assuming responsibility for civilian protection. Yet, the resurgence of M23 offensives in North Kivu and renewed ADF activity in Ituri quickly demonstrated the fragility of such transitions. Facing deteriorating security conditions, the UN Security Council extended MONUSCO’s mandate until 20 December 2025, explicitly characterizing it as an “exceptional” continuation of the intervention brigade and focusing deployments in North Kivu and Ituri (UNSC, 2024; UN Press, 2025).

From a liberal institutionalist perspective, the extension underscores how international institutions adapt to shifting conflict dynamics but is ultimately reactive rather than preventive. Institutions prolong their presence when systemic instability threatens wider regional order, reflecting both normative commitments to protection and strategic interests in avoiding a collapse that could destabilize Central Africa. Analytically, the drawdown debate reveals a paradox: MONUSCO’s presence provides immediate stability for IDPs and aid delivery, but its eventual departure, if not paired with robust local security capacity and humanitarian coverage, creates a vacuum where protection gaps quickly widen. Aid convoys stall, local markets close, and IDPs face heightened risks of extortion and attack when forced to move in search of food or safety. Conversely, targeted protection-of-civilians (PoC) tasks, such as escorts to fields and markets or so-called “Secure Harvest” patrols, have demonstrated measurable benefits for IDP livelihoods and dignity, suggesting that even a limited international presence can shape local survival strategies in ways that go beyond immediate deterrence (Reuters, 2024).

Gender and Vulnerability: A Necessary Deepening

A gendered analysis makes the stakes even clearer. Conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) has escalated alongside displacement surges around Goma. In early 2025, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) documented approximately 500 reported cases in a single week, almost certainly an undercount given stigma and reporting barriers. Data compiled by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) show an alarming rise from ~40,000 documented sexual violence cases in 2021 to over 113,000 by 2023, with women and girls constituting nearly 90 percent of survivors and an increasing proportion of child victims. These statistics highlight not only the scale of abuse but also the structural vulnerabilities created by displacement: overcrowded camps, insecure shelters, unlit latrines, and reliance on firewood collection or informal labor all heighten exposure to exploitation and assault.

MONUSCO’s record on addressing these gendered risks is mixed. On one hand, the mission has deployed female engagement teams, conducted patrols around water points and latrines, and collaborated with humanitarian partners to establish referral pathways for survivors. These actions resonate with the liberal institutionalist emphasis on norm diffusion by embedding global standards on gender protection into local practice; the mission sought to transform community expectations and institutionalize accountability. On the other hand, gaps remain acute. Services provided by UNFPA in 2025, mobile SRH/GBV clinics, safe spaces, and hotlines, are outpaced by demand, and many IDPs report that even where patrols exist, they are irregular or poorly communicated. Moreover, cases of survival sex in exchange for food or protection within camps illustrate how displacement governance itself can reproduce gendered hierarchies of power and vulnerability, raising questions about the institutional effectiveness of protection norms in contexts of scarcity and dependency.

Liberal institutionalism helps explain this contradiction: MONUSCO, as an international institution, successfully advanced global norms around the protection of women and children, but without sufficient resources, enforcement power, or sustained host-state support, the institutionalization of those norms faltered. In other words, while norms were articulated and formally embedded, their translation into consistent practice was undermined by the mission’s structural limits.

Analytical Takeaway

The experience of MONUSCO in eastern DRC provides a critical lens through which to evaluate the role of multilateral institutions in contemporary peacekeeping, particularly when measured against the theoretical expectations of Liberal Institutionalism. On one level, MONUSCO exemplifies the liberal claim that institutions matter: they create platforms for cooperation, reduce transaction costs among actors, and embed international norms into local practice. The very presence of blue helmets in conflict zones often alters the cost–benefit calculations of armed actors, making attacks on civilians or aid convoys riskier and less frequent. Evidence from North Kivu, where Rapid Reaction Forces (RRFs) and the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) disrupted over seventy planned assaults between 2018 and 2021, demonstrates the mission’s ability to alter immediate security dynamics. In these contexts, MONUSCO gave substance to the liberal institutionalist belief in “protection through presence”, the idea that institutions can constrain violence not only by coercion but also by shaping expectations, signaling global concern, and deterring potential perpetrators.

Yet these gains expose a deeper paradox. Institutions can temporarily modify behavior, but their ability to transform underlying structures of conflict is far more limited. MONUSCO’s short-term deterrence was consistently undercut by unresolved drivers of violence, including elite predation, competition over resource rents, and regional state support to insurgencies. From a liberal institutionalist perspective, this highlights a fundamental tension: institutions can embed norms and reduce incentives for violence, but in environments of weak sovereignty, fragile governance, and entrenched external interference, their influence is contingent, reversible, and ultimately fragile. In such cases, institutional design alone cannot overcome deficits in political will or the absence of credible enforcement mechanisms at the state and regional levels.

The drawdown process further illuminates the structural constraints of institutionalized peacekeeping. MONUSCO’s phased exit from South Kivu in June 2024, followed by the Security Council’s decision to extend its mandate in North Kivu and Ituri until December 2025, demonstrates the adaptive but reactive nature of multilateral institutions. Liberal institutionalism suggests that organizations persist because they serve collective interests; however, MONUSCO’s extension also reflected the inability of the Congolese state and regional security arrangements to provide effective substitutes. In this sense, MONUSCO was simultaneously indispensable and insufficient: indispensable because its absence risked immediate humanitarian collapse, yet insufficient because its presence, after two decades, had not resolved the structural conditions driving mass displacement. This reveals a gap between institutional resilience (the ability to adapt mandates, extend timelines, or reconfigure forces) and institutional effectiveness (the ability to produce durable security outcomes).

A further layer of analysis emerges when gender and displacement are foregrounded. Conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), disproportionately borne by women and girls in IDP camps around Goma, illustrates the implementation gap between global norms and field realities. On paper, MONUSCO was a carrier of universalist norms such as the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) and the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda. In practice, however, resource constraints, uneven patrol patterns, and weak accountability meant that women and adolescents remained acutely vulnerable, with over 113,000 documented sexual violence cases in 2023 alone (PHR, 2023). Liberal institutionalism posits that institutions serve as vehicles for norm diffusion, embedding human rights standards into conflict settings. MONUSCO did achieve norm diffusion, female engagement teams, safe spaces, and GBV referral pathways testify to this. Yet the translation of norms into consistent practice was undercut by logistical limits, donor fatigue, and the Congolese state’s own governance failures. Thus, the gendered dimension of displacement exposes the limits of institutionalist optimism: norms may be proclaimed, but without sustained capacity, enforcement, and accountability, they risk remaining symbolic rather than transformative.

What emerges is an institution caught between normative ambition and structural constraint. MONUSCO embodied the liberal institutionalist hope that collective action through multilateral frameworks can mitigate conflict and safeguard vulnerable populations. It provided real, measurable benefits, thwarted attacks, improved humanitarian access, local trust building, and the institutionalization of civilian-protection norms. Yet its experience also underscores the fragility of institutional power in environments where norms collide with entrenched material interests, where host-state consent is inconsistent, and where international political will fluctuates. As the drawdown continues, the dangers of a premature exit highlight that institutions cannot merely be judged on their presence but on their ability to leave behind resilient local structures capable of carrying forward the protection mandate.

In short, MONUSCO validates Liberal Institutionalism’s insight that international institutions matter profoundly in shaping conflict trajectories, but it also demonstrates the conditionality of institutional effectiveness. Where institutions are under-resourced, politically constrained, or embedded in weak state environments, their influence may be temporary rather than transformative. For policymakers, scholars, and practitioners, the lesson is clear: peacekeeping institutions can deter violence and embed humanitarian norms, but without parallel investments in governance reform, regional diplomacy, and local capacity-building, they remain vulnerable to the very fragilities they were designed to address.

Conclusion

Whether MONUSCO should be considered a success or failure remains one of the most contested questions in contemporary peacekeeping analysis, and the answer depends largely on the evaluative framework applied. From one perspective, MONUSCO can be deemed a qualified success: it provided immediate protection for millions of civilians, reduced violence in localized contexts, created space for humanitarian access, and embedded global protection norms such as R2P and the Women, Peace, and Security agenda in a notoriously unstable environment. Supporters of this view highlight tangible evidence of deterrence, such as the documented decline in civilian attacks following the deployment of Rapid Reaction Forces, and argue that without MONUSCO’s presence, the humanitarian catastrophe in eastern DRC would have been far more severe.

From another perspective, however, MONUSCO represents a cautionary tale of institutional limits. Despite over two decades of operations and billions in expenditures, the mission has not fundamentally altered the structural drivers of conflict, elite predation, regional interference, and competition over resource rents, which continue to fuel displacement and violence. Critics argue that MONUSCO has effectively managed crises without resolving them, providing “pockets of protection” rather than a durable pathway toward security or development. The persistence and indeed escalation of displacement, with more than 6.9 million IDPs recorded by late 2023, underscores the depth of the challenge. Moreover, gendered vulnerabilities, particularly the staggering rise in conflict-related sexual violence, expose the limits of institutional capacity to fully translate normative commitments into protective realities.

Thus, MONUSCO occupies an ambiguous space in peacekeeping scholarship and practice. Through a Liberal Institutionalist lens, it validates the central premise that institutions matter: they can shape behavior, spread norms, and provide forums for cooperation. Yet its mixed record also exposes the fragility of these achievements when international will wanes, host-state consent is unreliable, and resource allocations prioritize military presence over long-term governance reform and humanitarian resilience.

The debate over MONUSCO’s legacy is unlikely to be resolved soon. For optimists, it demonstrates that multilateral institutions can mitigate conflict and prevent catastrophic escalation even in “impossible” environments. For skeptics, it exemplifies the structural limits of peacekeeping missions that lack the mandate, resources, or political backing to transform the root causes of instability. Ultimately, the mission’s mixed record reveals a broader truth about contemporary peace operations: success is rarely absolute and often lies in the space between harm reduction and transformative change. As the drawdown proceeds, the international community faces a critical question: whether the lessons of MONUSCO will be integrated into future peacekeeping models, or whether the cycle of ambitious mandates and constrained delivery will continue to define the UN’s approach to protecting vulnerable populations in protracted crises.

Disclaimer

This analytical reflection post is based on my thesis research, defended at the University of Warsaw, Faculty of Political Sciences and International Studies, as part of the fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree in International Relations (July 2024). The analysis presented here deliberately focuses on one angle of MONUSCO’s engagement in eastern DRC: its role in internally displaced persons (IDPs). It does not attempt to capture the entirety of MONUSCO’s mandate or institutional narrative but instead reflects on the academic reality and evidence-based truth of how IDP protection has been framed, implemented, and contested within the mission. The insights provided here are thus not institutional statements but scholarly reflections that situate MONUSCO within the broader debates of peacekeeping, humanitarian protection, and liberal institutionalist theory.