The Horn of Africa has become a global epicenter of climate-induced displacement, where recurrent droughts and failed rainy seasons intersect with fragile governance and ongoing conflicts. Between 2020 and 2024, drought displaced more than 3.5 million people across Somalia, Ethiopia, and Kenya, exacerbating food insecurity, undermining livelihoods, and straining already fragile peace and security environments. This reflection examines the nexus between human mobility, climate adaptation, and security governance, using recent trends in displacement and policy responses as empirical anchors.

Applying a human security lens, the analysis highlights how mobility, often framed as a destabilizing threat, should instead be recognized as a legitimate form of adaptation. National responses, such as Kenya’s drought management strategies and Ethiopia’s fragmented IDP policies, demonstrate partial progress but remain reactive. Regional frameworks under IGAD offer normative recognition of climate mobility but lack operational depth, while international donor interventions often prioritize containment over adaptation.

The findings reveal three persistent policy gaps: reactive governance, securitization of mobility, and exclusion of vulnerable groups, particularly women and children, who represent nearly 80% of displaced populations. Reframing human mobility as adaptation rather than insecurity is essential to link climate resilience with peacebuilding, ensuring that displacement becomes a survival pathway, not a source of further instability.

Drought, Displacement, and the Policy Dilemma

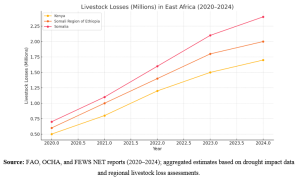

The Horn of Africa epitomizes the convergence of climate fragility, human insecurity, and weak governance capacity. The region has experienced five consecutive failed rainy seasons (2022–2023), triggering the displacement of an estimated 2.1 million people across Somalia, Ethiopia, and Kenya (IDMC, 2023). In Somalia alone, more than 6.6 million people are currently classified as acutely food insecure, while pastoralist communities in Ethiopia and northern Kenya have lost nearly nine million livestock, a devastating erosion of livelihoods and cultural identity (FAO, 2023).

These figures underscore that the crisis is not solely ecological, but rather deeply political and institutional. Displacement in the Horn cannot be understood merely as a humanitarian emergency; it is a profound governance dilemma. At its core lies the question of how States and regional bodies respond to mobility: do they treat movement as a form of adaptive resilience, or do they frame it as a threat to stability and order?

The concept of bureaucratic bordering, the use of administrative tools to regulate and restrict movement, offers an important analytical lens. National governments across the Horn have often defaulted to restrictive practices, securitizing mobile populations, particularly pastoralist groups, rather than facilitating their adaptive strategies. Regional initiatives, such as those led by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), have rhetorically acknowledged climate mobility but remain slow in operationalizing protection frameworks. This reveals a critical gap between policy discourse and practice, in which displacement is managed reactively and selectively rather than integrated into long-term resilience planning.

As such, the Horn of Africa stands at a crossroads. The region’s policy dilemma encapsulates a broader global challenge: whether to integrate climate-induced mobility into adaptive governance frameworks or to allow securitized logics to prevail. The stakes are high, not only for displaced populations but also for regional peace and security, as unmanaged mobility risks amplify inter-communal tensions, fueling recruitment into armed groups, and deepening fragility. Framing mobility as an inevitable and legitimate adaptation strategy, rather than as a destabilizing force, will determine whether the region can navigate the next decade of climate shocks with resilience or with renewed instability.

Climate Mobility through a Human Security Lens

The human security paradigm provides a valuable framework for analyzing drought-induced displacement in the Horn of Africa, as it shifts the analytical lens from the State to the individual. Unlike traditional, state-centric conceptions of security that emphasize territorial sovereignty and regime stability, the human security approach popularized by the UNDP Human Development Report (1994) and expanded by scholars such as Paris (2001), prioritizes the protection of lives, livelihoods, and human dignity. From this perspective, mobility is not merely a byproduct of crisis but an active strategy of adaptation, deployed by individuals and communities to mitigate climate risks and secure survival.

However, State and regional policy frameworks across the Horn of Africa often fail to embrace this human security logic. Instead, they revert to what Huysmans (2006) and Buzan, Wæver & de Wilde (1998) describe as the securitization of migration, the framing of human mobility as a destabilizing phenomenon requiring restriction and control. This manifests in border militarization, restrictive residency regimes, and bureaucratic obstacles that reduce mobility to a “risk factor” rather than an adaptive resource. Such responses align more closely with state security paradigms that prioritize sovereignty over human well-being.

The implications of this tension are significant. The IGAD Climate Prediction and Applications Centre (ICPAC) estimates that by 2030, droughts could displace more than 10 million people regionally, a figure that will exacerbate existing border tensions between Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia. Left unaddressed, such large-scale movements could amplify competition over scarce resources, increase inter-communal violence, and undermine fragile peace processes. Yet most national migration policies in the region remain reactive, limited to emergency food aid or temporary camp-based solutions, rather than adaptive frameworks that integrate mobility into long-term resilience planning.

This disjuncture highlights a structural governance gap: the failure to institutionalize mobility as adaptation. While mobility has long been part of pastoralist coping strategies in the Horn, modern policy regimes treat it as an exception to be managed rather than a legitimate survival mechanism to be supported. As Black et al. (2011) emphasize in their framework on migration and environmental change, human mobility must be seen not only because of vulnerability but also as a contributor to resilience if properly enabled by policy. In the absence of such enabling structures, displacement risks perpetuating cycles of insecurity, where climate shocks trigger forced mobility, which in turn fuels social and political instability.

In short, the application of the human security lens exposes a core contradiction: while communities mobilize movement as an adaptive response to climate stress, States securitize the same behavior, producing policies that criminalize survival strategies. This tension illustrates the stakes of governance in the Horn of Africa: whether displacement will be embedded within adaptive resilience frameworks or entrenched as a source of insecurity and exclusion.

Policy Responses: Adaptation or Exclusion? – Navigate National Approaches: Kenya Vs Somalia Vs Ethiopia

Kenya is often cited as a pioneer in the region for establishing the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA) in 2011, which has developed resilience programming and early warning systems for drought-prone areas. Yet, despite these advances, NDMA’s framework has not adequately embedded mobility rights for pastoralists. Groups such as the Turkana and Somali herders depend on seasonal cross-border mobility with Ethiopia and Somalia as a centuries-old coping strategy. Instead of institutionalizing these movements within legal frameworks, Kenyan authorities continue to regulate them through ad hoc border closures and security interventions, particularly in times of heightened resource scarcity. This tension highlights the contradiction identified by de Haas (2014) in migration governance: States simultaneously depend on and restrict mobility, revealing a structural ambivalence between economic necessity and securitization.

Ethiopia’s case illustrates the limits of fragmented governance in a federal state. Successive droughts displaced approximately 1.5 million people between 2022 and 2023 (IDMC, 2023), yet policies remain split between federal disaster management agencies and regional authorities, particularly in Oromia and Somali regions. This fragmentation leads to inconsistent assistance, with some regions prioritizing food aid while others pursue relocation schemes. The weakness of Ethiopia’s IDP Policy (2019), poorly resourced and rarely enforced, reflects the “implementation gap” described in policy implementation theory (Pressman & Wildavsky, 1984), where institutional promises remain unfulfilled on the ground. The federal government’s focus on counter-insurgency, particularly in Tigray and Oromia, has further securitized displacement responses, diverting resources away from resilience planning.

At the other side, Somalia’s weak governance capacity exacerbates the interplay between climate shocks and insecurity. Humanitarian corridors exist, often facilitated by international actors such as WFP and UNHCR, yet displacement camps frequently become sites of contestation and recruitment for Al-Shabaab. This dynamic underscores Kalyvas’ (2006) observation that non-state armed groups exploit humanitarian vacuums to consolidate authority. In practice, unmanaged mobility in Somalia has become not only a humanitarian challenge but also a security multiplier, as displaced populations are caught between aid dependence and political manipulation.

Regional and International Responses

At the regional level, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) has emerged as a normative leader, particularly through its Migration Policy Framework (2012, updated 2021) and the Free Movement Protocol (2020). Both instruments explicitly acknowledge the role of climate mobility. However, their operationalization remains weak, as national governments often resist cross-border mobility provisions for fear of undermining sovereignty. This gap illustrates what Betts (2011) calls the “governance paradox”: regional frameworks exist but are undercut by national interests and political calculations.

Internationally, donor-funded initiatives like the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa claim to focus on resilience but still prioritize containment and deterrence in practice. Projects are often aimed at preventing outward migration to Europe rather than improving adaptive mobility within the region. This demonstrates the “externalization of migration control” critique raised by Andersson (2014) and Crawley & Skleparis (2018), where European interests influence African migration policies. The paradox is evident: although resilience is emphasized in policy language, deterrence remains the main approach.

Mobility at the Crossroads of Peace and Security

The Horn of Africa vividly illustrates how climate-induced displacement acts as a conflict multiplier, amplifying pre-existing fragilities in societies already struggling with weak governance and recurrent violence. While humanitarian narratives often frame displacement as a neutral emergency requiring relief, a closer analysis reveals that unmanaged mobility not only exacerbates social tensions but also generates new forms of insecurity. This duality reflects what Homer-Dixon (1999) termed the “environmental scarcity–conflict nexus,” whereby resource stress interacts with fragile political systems to intensify conflict dynamics. In the Horn, drought-induced mobility is neither temporary nor exceptional; it is increasingly a structural feature of political and security landscapes.

In Somalia, the intersection between climate shocks, displacement, and violent extremism is particularly stark. Recurrent droughts have displaced millions, creating sprawling camps around urban centers such as Baidoa and Mogadishu. While these camps function as humanitarian spaces providing food aid and shelter, they have simultaneously become sites of recruitment and manipulation by Al-Shabaab. The militant group exploits the desperation of displaced populations, offering basic services or coercive incentives in exchange for allegiance. Moreover, competition over dwindling resources, particularly pastureland and water points, has intensified clan rivalries, deepening inter-communal violence. This dynamic underscores Kalyvas’ (2006) argument that armed groups thrive in contexts where governance vacuums coincide with humanitarian crises. Somalia, therefore, exemplifies how unmanaged displacement operates as a conduit linking environmental stress to both local and transnational insecurity.

In Ethiopia’s Somali Region, mobility itself has become securitized. Historically, pastoralist groups relied on cross-border transhumance as a primary adaptation strategy during drought cycles, moving livestock seasonally between Ethiopia, Somalia, and Kenya. However, in the post-2015 period, Ethiopian authorities increasingly deployed military patrols and border controls to restrict this mobility, particularly amid heightened counter-insurgency campaigns. This reflects what Huysmans (2006) conceptualizes as the securitization of migration: adaptive strategies traditionally embedded in pastoralist livelihoods are reframed as threats to state security. The militarization of borders not only criminalizes longstanding cultural practices but also heightens inter-state tensions, as accusations of cross-border infiltration or resource theft generate diplomatic friction. This process reveals the broader paradox of climate mobility in fragile states: while movement is essential for survival, state policies increasingly treat it as illegitimate, thereby deepening rather than reducing insecurity.

Kenya provides yet another angle on this mobility–security nexus, where localized conflict has escalated as drought constrains pastoralist options. Counties such as Turkana, Marsabit, and Wajir have long experienced cyclical clashes over pasture and water. Yet, climate stress has magnified these disputes, turning them more violent and protracted. According to ACLED (2023), drought-affected counties in Kenya witnessed a 40% increase in inter-communal clashes compared to non-affected regions, illustrating the compound fragility that emerges when environmental shocks intersect with governance deficits. Localized conflicts are further exacerbated by the proliferation of small arms, weak enforcement of early-warning mechanisms, and limited State presence in peripheral borderlands. This aligns with the “conflict trap” thesis (Collier et al., 2003), where recurring violence undermines governance, which in turn perpetuates the conditions for renewed conflict. Thus, rather than facilitating peaceful adaptation, the restriction of mobility fuels new cycles of violence and displacement.

Taken together, these cases show that the peace–security consequences of climate mobility in the Horn are contingent on governance choices. Where mobility is obstructed or securitized, displacement fuels insecurity by intensifying competition, enabling armed group recruitment, and triggering localized conflict. Where mobility is recognized as adaptation, the risks of violence are reduced. Yet most policy frameworks continue to prioritize sovereignty and control over human security and resilience, perpetuating the cycle of insecurity. The Horn of Africa, therefore, offers an empirical case for rethinking mobility not as a destabilizing force but as a governance challenge: the extent to which States and regional organizations institutionalize mobility as adaptation will determine whether displacement contributes to peace or precipitates further instability.

Conclusion: Towards Mobility as Adaptation

The evidence from the Horn of Africa underscores that human mobility in drought-prone regions must be reframed as a legitimate and proactive form of adaptation, rather than a symptom of humanitarian failure. To persist in viewing displacement as an aberration or threat is to ignore the long historical role of movement in sustaining pastoralist livelihoods and mitigating environmental shocks. As Black et al. (2011) remind us, migration is not only a consequence of vulnerability but can also be a pathway to resilience, provided it is enabled by appropriate governance frameworks.

Realizing this vision demands a paradigm shift from containment to resilience. At the regional level, this involves embedding mobility within cross-border agreements under IGAD, ensuring that pastoralist groups can move safely, legally, and predictably in pursuit of water and grazing. At the national level, programming must go beyond food aid to address the gendered vulnerabilities of displacement, integrating protection against sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) while creating economic opportunities that strengthen women’s agency. Finally, mobility must be mainstreamed into peacebuilding frameworks, recognizing that unmanaged displacement often exacerbates inter-communal violence and can be exploited by armed groups.

The stakes are high. Without such shifts, the Horn risks institutionalizing precarity, where mobility is criminalized and pastoralist strategies of adaptation are delegitimized. This not only entrenches cycles of poverty and displacement but also destabilizes already fragile peace and security systems. Conversely, by reimagining mobility as adaptation, policymakers can transform displacement from a destabilizing force into a foundation for resilience. The policy imperative is therefore clear: in an era of intensifying climate shocks, treating mobility as adaptation is not simply a humanitarian necessity but a strategic prerequisite for sustainable peace, security, and human dignity in the region.

References & Sources Consulted

To publish this reflection, I engaged with a range of academic and policy sources that provided both theoretical and empirical insights. Homer-Dixon (1999) offered the analytical foundation on environmental scarcity as a catalyst for violence, which helped frame displacement as a conflict multiplier. The concept of securitization of migration, as developed by Huysmans (2006) and expanded by Buzan, Wæver & de Wilde (1998), shaped the discussion on how States reframe adaptive mobility as a security threat. Empirical displacement figures and humanitarian data were drawn from the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC, 2023) and FAO (2023), which highlighted the scale of drought-induced displacement and livestock losses. The ACLED dataset (2023) provided evidence linking drought-affected areas in Kenya with increased inter-communal clashes, reinforcing the conflict–mobility nexus. Finally, regional and institutional perspectives, particularly through IGAD’s Migration Policy Framework (2012, updated 2021) and the Free Movement Protocol (2020), informed the discussion on policy responses, while the critical reflections of Black et al. (2011) emphasized mobility as both vulnerability and resilience. Together, these sources anchored the analysis in both theory and practice, allowing me to examine mobility in the Horn of Africa through the combined lenses of human security, governance, and peacebuilding

Disclaimer & Engagement Note

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do not represent the official positions of any government, organization, or institution with which the author has been affiliated. These writings are intended for academic reflection and public dialogue.

👉 Are you a policymaker, institution, or academic interested in engaging on these issues, or seeking consultation? Please fill in the contact form to connect.