Climate change is increasingly recognized as a driver of migration, yet global governance frameworks struggle to accommodate this reality. This reflection examines Malawi as an empirical anchor for understanding the paradoxes of climate displacement. Since 2019, floods and cyclones have displaced nearly one million Malawians, but less than 1% have been permanently relocated through formal programs. Using the lens of human security, the analysis argues that displacement in Malawi exemplifies “silent mobility”: not dramatic refugee exoduses, but the slow erosion of livelihoods that gradually forces people to move. The reflection situates Malawi’s adaptation failures within a global comparative mirror, drawing parallels with the securitized approaches of the European Union, the United States, and Canada. While states increasingly treat mobility as a failure to adapt, this piece argues that migration must be recognized as a legitimate adaptation strategy, central to resilience in a climate-unstable world. By reframing displacement through human security rather than border security, policymakers can better align adaptation and mobility. The findings contribute to the scholarship on migration governance and climate security, while offering practical insights for reorienting international responses toward protecting people rather than merely containing movement.

A Local Crisis with Global Echoes

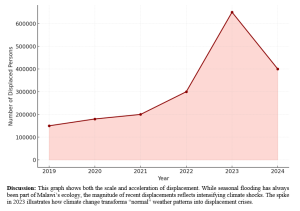

In March 2023, Cyclone Freddy tore across Southern Africa, displacing more than 650,000 Malawians in a single season and leaving over 500,000 hectares of farmland destroyed. Malawi, already one of the world’s poorest countries, found itself grappling with a humanitarian crisis that was both sudden and cumulative in nature. Since 2019, repeated floods and storms have uprooted nearly one million people, yet fewer than 10,000 households have been resettled through official programs (OCHA, 2023). For many, return is not possible, but underfunding, political sensitivities, and limited land availability stall relocation pathways.

This governance gap is not unique to Malawi. Across the Global South, climate displacement is accelerating, but institutional responses remain fragmented. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (2023) estimates that over 32 million people worldwide were displaced by climate-related disasters in 2022 alone, the majority in low-income countries. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where agriculture remains highly climate-dependent, climate hazards overlap with structural poverty, conflict, and weak state capacity, creating what scholars have described as “complex displacement” (Boas, 2015).

The paradox is global. In Europe, migration governance increasingly ties aid to border control, externalizing responsibility to African states (Betts, 2011; Andersson, 2014). In the United States, climate migration is rhetorically acknowledged but practically subsumed under border security frameworks. In Canada, policy statements frame climate mobility as a humanitarian issue, but resettlement remains symbolic, numbering in the hundreds rather than thousands. These patterns underscore a shared blind spot: while mobility is inevitable under worsening climate impacts, it is politically framed as a failure of adaptation rather than an adaptive strategy in its own right.

This piece argues that the human security framework provides a more effective conceptual anchor for understanding and responding to climate displacement. Unlike State-centric approaches that prioritize territorial sovereignty, human security emphasizes “freedom from want” and “freedom from fear,” centering the lived vulnerabilities of individuals and communities (UNDP, 1994). Applying this lens to Malawi illuminates how displacement is less about dramatic refugee flows and more about the slow erosion of everyday life: farmland washed away, schools submerged, youth migrating for survival.

By situating Malawi’s “silent displacement” within a global comparative mirror, this piece contributes to three interlinked debates. (1) It extends climate migration scholarship by highlighting under-examined African cases outside the Sahel or Horn of Africa. (2), It bridges theoretical and policy discussions by showing how human security can reframe adaptation beyond securitized logics. (3), it provides a critical reflection for policymakers in both the Global South and North: unless mobility is recognized as adaptation, climate governance will remain reactive, fragmented, and ultimately unsustainable.

Theorizing the situation: Human Security vs. Securitization

The framing of climate-induced displacement has long oscillated between two dominant lenses: human security and securitization. Each offers distinct insights but also reveals the normative stakes at play in how migration governance is designed.

The human security framework, introduced in the 1994 UNDP Human Development Report, redefined security beyond the traditional focus on state sovereignty. Rather than prioritizing territorial integrity, it emphasized the security of individuals and communities through seven interlinked dimensions: economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political security. This approach was groundbreaking in recognizing that insecurity does not only arise from armed conflict or interstate war but also from structural vulnerabilities such as poverty, hunger, and natural disasters (UNDP, 1994). In the context of climate displacement, human security underscores that the true risks lie in the erosion of livelihoods, food insecurity, and the collapse of coping capacities.

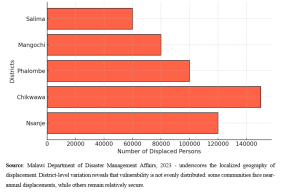

Applied to Malawi, this framework reveals the everyday insecurities of climate-displaced communities. Families in Nsanje or Chikwawa are not primarily threatened by state borders but by recurrent flooding, which sweeps away farmland, destroys schools, and cuts off markets. Displacement, whether internal or cross-border, becomes a strategy to re-establish “freedom from want.” Yet migration governance in Malawi often neglects this perspective. Resettlement schemes are underfunded, and international support arrives primarily in the form of emergency relief rather than sustained livelihood protection. A human security approach would shift the focus from short-term humanitarian response to long-term resilience planning, integrating mobility into adaptation strategies.

By contrast, securitization theory, rooted in the Copenhagen School (Buzan, Wæver, & de Wilde, 1998), examines how political actors frame certain issues as existential threats, thereby justifying extraordinary measures. In migration governance, securitization manifests in the portrayal of migrants as risks to national identity, economic stability, or territorial integrity. Climate mobility is increasingly subject to this process, particularly in the Global North.

In the European Union, migration from Africa is frequently framed as a destabilizing force, leading to policy instruments such as the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, which ties development aid to containment measures (Castles, de Haas, & Miller, 2014). In the United States, climate displacement from Central America is discussed primarily in the context of border security, with funding directed toward enforcement rather than adaptation partnerships. Even in Canada, often celebrated for progressive immigration policies, climate migration is framed as a niche humanitarian issue, symbolic rather than systemic.

These contrasting frameworks matter because they shape policy outcomes. A human security lens legitimizes mobility as adaptation and encourages investment in safe pathways, proactive resettlement, and livelihood diversification. A securitization lens, however, casts mobility as a threat, leading to militarized borders, externalized containment, and reactive humanitarianism. Malawi exemplifies the consequences of neglecting human security: displacement becomes protracted, adaptation options shrink, and migration is stigmatized rather than supported.

The theoretical contribution of this reflection is therefore twofold. First, it argues that human security provides a more normatively and analytically useful framework for addressing climate displacement. Second, it shows that securitization remains the dominant paradigm in both domestic (Malawi) and international (EU, U.S., Canada) governance responses. The tension between these two logics, people-centered vs. border-centered, constitutes the central paradox of climate migration politics.

Case Study: Malawi – Silent Displacement and Adaptation Failures

Malawi, a landlocked country of roughly 20 million people, is one of the most climate-vulnerable nations in the world. Ranked among the top ten on the Global Climate Risk Index, Malawi faces recurrent hazards ranging from droughts to devastating floods. Its economy is overwhelmingly agrarian, with over 80 percent of the population dependent on rain-fed agriculture for food and livelihoods (World Bank, 2022). This structural dependence makes the population acutely sensitive to even minor shifts in rainfall, let alone catastrophic cyclones.

Since 2019, climate disasters have displaced nearly one million Malawians, with floods and cyclones accounting for the majority of cases (OCHA, 2023; IDMC, 2023). The most severe was Cyclone Freddy in 2023, which displaced over 650,000 people in a single season, damaged 1,000 schools, and destroyed over half a million hectares of farmland. While global attention focused briefly on the storm’s unprecedented ferocity, it was one of the longest-lasting tropical cyclones ever recorded, and the subsequent displacement crisis quickly faded from international headlines.

Graph 1: Annual Displacement in Malawi (2019–2024) : Source: UN OCHA, 2023; IDMC, 2023. Figures are rounded estimates

Certain districts withstand the worst of these disasters. Nsanje and Chikwawa, located in Malawi’s southern Shire Valley, experience recurrent flooding due to low-lying geography. Phalombe, nestled at the base of Mulanje Mountain, suffers from mudslides and flash floods. Mangochi and Salima, situated along Lake Malawi, face both floods and prolonged dry spells. Meanwhile, Malawi’s government has acknowledged the challenge through its National Resilience Strategy (2018–2030), which identifies disaster preparedness, food security, and relocation as priorities. However, implementation has lagged. Resettlement programs have been especially inadequate. Fewer than 10,000 households have been permanently relocated in the past decade, less than one percent of those displaced (Government of Malawi, 2022).

Certain districts withstand the worst of these disasters. Nsanje and Chikwawa, located in Malawi’s southern Shire Valley, experience recurrent flooding due to low-lying geography. Phalombe, nestled at the base of Mulanje Mountain, suffers from mudslides and flash floods. Mangochi and Salima, situated along Lake Malawi, face both floods and prolonged dry spells. Meanwhile, Malawi’s government has acknowledged the challenge through its National Resilience Strategy (2018–2030), which identifies disaster preparedness, food security, and relocation as priorities. However, implementation has lagged. Resettlement programs have been especially inadequate. Fewer than 10,000 households have been permanently relocated in the past decade, less than one percent of those displaced (Government of Malawi, 2022).

Graph 2: Malawi Districts Most Affected by Floods & Cyclones (Displaced Persons 2019-2024)

Livelihood Erosion and “Silent Displacement”

Livelihood Erosion and “Silent Displacement”

Unlike refugee crises characterized by mass exodus, Malawi’s climate displacement is erosional and protracted. Families oscillate between damaged homes, temporary shelters, and seasonal migration. Youth increasingly seek opportunities abroad, particularly in Mozambique and South Africa, where remittances become survival lifelines. Internal migration toward urban centers like Blantyre and Lilongwe also rises during crises, stressing fragile infrastructure and labor markets.

This form of displacement is often invisible in global debates. It does not produce the kind of dramatic refugee images that capture international media attention, yet its cumulative effects are profound. Food insecurity worsens, Malawi already ranks among the most undernourished populations globally, and education is disrupted as schools double as emergency shelters. Social protection systems are too thinly stretched to cushion affected households.

Scholars describe this as “silent displacement” (Zetter, 2017): a slow-moving erosion of options where people move not out of choice but because every alternative, farmland, housing, safety nets, fails. Silent displacement challenges dominant refugee-centered frameworks by emphasizing adaptation failure within national borders.

The Human Security Lens Applied to Malawi & Implications for Global Debates

Through the human security lens, the Malawi case highlights how climate displacement undermines basic freedoms. “Freedom from want” is threatened by destroyed crops and collapsing markets. “Freedom from fear” is compromised by recurrent exposure to floods and the uncertainty of rebuilding in precarious zones. Communities repeatedly displaced experience not only material loss but psychological strain, with trauma compounding over successive disasters.

Yet national and international policy frameworks remain rooted in securitization logics. Internal relocation is politicized, while external migration is viewed with suspicion. Instead of normalizing mobility as resilience, governance mechanisms treat displacement as a temporary disruption. This leaves communities trapped in cycles of precarity.

Malawi’s case complicates the global climate migration discussion in three ways. First, it shows that climate displacement is not just about dramatic crises but also about the slow loss of livelihoods in “silent” contexts. Second, it highlights that national adaptation efforts are insufficient without international burden sharing. Malawi alone cannot bear the financial and social costs of repeated mass displacement. Third, it reveals how failing to reframe mobility as a form of adaptation deepens vulnerability.

Global Mirror: EU, U.S., Canada Vs the Horn of Africa Comparison

Malawi’s governance gaps are not exceptional; they mirror global patterns in climate migration politics. Across regions, the dominant response is not to integrate mobility into adaptation strategies but to contain it within securitized frameworks.

In the European Union, the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa channels billions into border control and return agreements, while less than five percent supports proactive adaptation or labor mobility schemes (European Commission, 2016). Migration is framed primarily as a threat to stability, even as Europe’s agricultural sector depends on seasonal African labor.

The United States recognizes climate change as a “threat multiplier,” but in practice, policy remains tied to border enforcement. Funding for climate adaptation in Central America is overshadowed by security budgets exceeding USD 2 billion annually (US DHS, 2023). Migrants fleeing drought in Honduras or flooding in Guatemala are encountered not as adaptation actors but as border crossers.

Canada presents a more progressive discourse, pledging pathways for climate-displaced persons. Yet resettlement numbers remain symbolic, measured in hundreds rather than systemic programs. Overseas assistance also prioritizes resilience-building projects but rarely scales to meet the magnitude of displacement needs.

Even within Africa, securitization persists. In the Horn of Africa, drought-induced displacement pushes Somalis into Ethiopia and Kenya, but regional responses focus on temporary encampment rather than mobility as resilience. The parallels to Malawi are stark: communities move because they must, while governance frameworks remain wedded to containment.

Conclusion

From Malawi’s floodplains to Europe’s Mediterranean borders and the Horn of Africa’s drought corridors, the story is consistent: mobility is inevitable, yet governance treats it as failure. The securitization of climate displacement entrenches precarity, leaving communities oscillating between disaster zones and temporary shelters.

The human security approach points to an alternative. By reframing migration as adaptation, governments could invest in safe mobility pathways, proactive relocation, and livelihood diversification. This requires shifting resources away from containment and toward resilience.

The normative message is clear: in a climate-unstable world, the task is not to prevent movement but to govern it humanely. Climate displacement must be recognized not as a breakdown, but as a legitimate strategy of survival. Only by securing people before borders can global governance rise to the challenge of climate migration.

Disclaimer

This piece of reflection is based on my academic readings and analytical insights, and represents an independent scholarly perspective. It does not speak on behalf of any institution but is grounded in academic analysis and publicly available sources. The Malawi case is presented as one illustrative example within wider debates on climate displacement and governance, without claiming to capture the entirety of national or institutional narratives. The piece reflects an academic reality rather than an official position and is informed by my research ethics and scholarly trajectory. If you would like to access the full list of references and supporting materials used in this analysis, please press the Contact Us button.