Sub-Saharan Africa stands at the convergence of two monumental crises: protracted violent conflict and intensifying climate variability. While armed violence has historically dominated displacement narratives, a rising tide of climate-induced displacement is now reshaping mobility patterns across the region. Emerging data from the UNHCR and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) indicate that Africa is home to more than 80% of the world’s climate-related internal displacements. Droughts, floods, crop failures, and food insecurity are accelerating population movements at a rate far exceeding that of conflict alone. This short analytical paper critically examines the scale, causality, and policy responses surrounding climate-induced displacement, employing a multi-scalar, interdisciplinary lens. By analyzing quantitative data trends and qualitative case studies (Somalia, South Sudan, Mozambique), it demonstrates how climate shocks act not only as acute triggers but also as chronic structural forces of migration. The paper further proposes an updated framework for migration governance, one that integrates climate adaptation, anticipatory humanitarianism, and legal recognition of climate displacement.

Conceptualize the situation

In recent decades, the African continent, particularly its Sub-Saharan region, has emerged as a critical epicenter in global discussions on displacement, vulnerability, and humanitarian crises. Traditionally, narratives around forced migration from the region have been dominated by the specter of armed conflict: civil wars, insurgencies, ethnic violence, and political repression. However, this mono-causal explanation is increasingly insufficient in explaining the evolving realities on the ground. A significant and often underestimated force has entered this equation: climate change. The intensification of environmental stressors, prolonged droughts, erratic rainfall patterns, cyclonic storms, floods, and extreme heat is not only reshaping ecosystems but also directly disrupting human settlements, livelihoods, and migratory patterns.

As recent data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) reveal, Africa is now responsible for over 80% of the world’s climate-related internal displacement. In 2023 alone, more than 6.3 million individuals were internally displaced due to environmental factors, a figure that has increased sixfold since 2009 (Reuters, 2023). This shift signals a profound transformation in the drivers of displacement across the continent. Unlike armed conflict, which often erupts suddenly and draws international attention, climate-induced displacement is frequently slow-onset, invisible in policy discourse, and inadequately addressed by humanitarian frameworks.

This note, therefore, seeks to pose a central and underexplored question: To what extent is climate change transforming the nature, scale, and governance of internal displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa? It further asks: What are the implications of this shift for regional and global migration governance frameworks, humanitarian response models, and long-term adaptation planning? These questions are not merely academic; they lie at the intersection of development policy, international law, and climate justice.

Importantly, the publication does not treat climate change as an isolated trigger of displacement, but as a structural and compounding force. It draws on the analytical framework proposed by Mezzadra and Neilson (2013), who conceptualize borders not solely in geographical terms but as dynamic, systemic processes shaped by labor, inequality, and mobility governance. Within this lens, climate becomes a new axis of bordering, a determinant of who moves, where, and under what conditions. As environmental thresholds are crossed, entire regions become uninhabitable or economically unviable, prompting involuntary movement that does not necessarily align with conventional categories of refugeehood or asylum.

Moreover, the climate–conflict nexus is increasingly evident across multiple African contexts. Environmental degradation is rarely the sole cause of displacement; rather, it operates in tandem with governance failures, livelihood precarity, and social fragmentation. For instance, prolonged droughts in the Sahel have intensified competition over diminishing grazing land, leading to violent clashes between pastoralist and agrarian communities. In regions like northern Mozambique or South Sudan, climate hazards intersect with armed insurgency, generating complex emergencies that blur the line between conflict-induced and climate-induced displacement.

This paper adopts a multi-scalar, interdisciplinary approach, combining quantitative displacement data with qualitative case studies from Somalia, South Sudan, and Mozambique. It traces the pathways through which climate shocks translate into displacement, critically analyzes the policy gaps within existing humanitarian responses, and concludes with actionable recommendations aimed at reconfiguring displacement governance to include environmental drivers as central, not exceptional, concerns.

As climate change accelerates and adaptive capacities remain unevenly distributed, the urgency to re-conceptualize displacement becomes not only a matter of academic importance but also a humanitarian imperative. Without such a reconceptualization, millions will continue to fall through the cracks of legal recognition, policy protection, and sustainable resettlement options. By foregrounding climate as both a trigger and a structural condition, this publication contributes to a growing body of scholarship that calls for a more holistic and anticipatory understanding of mobility in the era of planetary crisis.

The scale & acceleration of climate displacement

The phenomenon of climate-induced displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa has transitioned from a peripheral humanitarian concern to a central challenge of the 21st century. Over the past decade and a half, the region has experienced a significant increase in the number of individuals displaced from their homes due to environmental disruptions. Climate-related factors, most notably prolonged droughts, catastrophic flooding, cyclonic storms, and increasingly erratic rainfall, have been displacing populations at an accelerating rate. This trend not only reflects the growing severity of climate events themselves, but also the deepening structural vulnerabilities that hinder communities’ capacity to adapt in place. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) reports that climate-induced internal displacement in Africa increased from approximately 1.1 million people in 2009 to over 6.3 million by 2023, representing a sixfold rise in just 14 years. This trajectory highlights a non-linear and compounding crisis, in which environmental volatility acts in tandem with poverty, underdevelopment, and governance fragility, forcing migration.

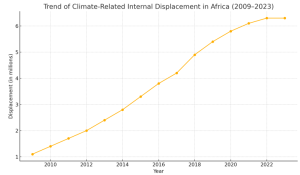

Graph 1. Climate-Related Displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa

Source: Author’s source after compilation of existing data – The alarming upward trend. From 2009 to 2023:

- The total number of climate-displaced persons increased by over 470%.

- The average annual growth rate of displacement is approximately 12%, reflecting intensifying vulnerability.

- The data reveal non-linear acceleration, with particularly steep increases post-2015, corresponding to El Niño-linked droughts and major flooding events.

Graphical representations of displacement trends between 2009 and 2023 reveal that the curve of displacement is not gradual but steep, particularly in the years following 2015, a period marked by intensified El Niño weather events and record-breaking droughts in the Horn of Africa. The average annual growth rate of climate-related displacement in the region is estimated to be over 12%, a figure that not only underscores the scale of the crisis but also the inadequacy of current humanitarian systems to keep pace. Unlike conflict, which often sparks episodic waves of displacement, climate-induced migration tends to be more protracted, recurrent, and geographically expansive. As climatic thresholds are surpassed more frequently, entire ecosystems lose their ability to support human habitation. In regions dependent on rain-fed agriculture and pastoralism, environmental degradation translates almost directly into livelihood collapse and involuntary migration.

Sub-Saharan Africa now accounts for an astonishing 80% of global climate-related internal displacements, a disproportionate burden given the continent’s minimal contribution to historical carbon emissions. According to the UNHCR’s 2024 estimates, out of the 223 million people displaced by climate worldwide in the past decade, a striking number have come from African nations. This discrepancy reveals a glaring climate justice deficit: those least responsible for planetary warming are the most exposed to its consequences. Within Africa, displacement is particularly concentrated in a few highly affected countries. Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan together account for nearly two million displacements annually due to climate-induced events such as severe droughts and flash floods. Mozambique, vulnerable to seasonal cyclones and rising sea levels, has experienced increasingly frequent mass evacuations, including over 100,000 displaced persons in just the first half of 2025 alone.

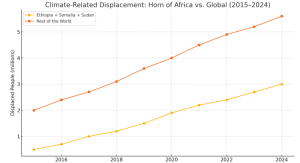

Graph 2. Climate Displacement: Horn of Africa vs. The Rest of the World (2015–2024)

Source: Author’s source after compilation of existing data – The chart above compares estimated climate-related internal displacement in Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan against the rest of the world over the past decade.

Source: Author’s source after compilation of existing data – The chart above compares estimated climate-related internal displacement in Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan against the rest of the world over the past decade.

- The Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan) shows a consistent and steep rise, reaching an estimated 3 million displaced people in 2024.

- These three countries alone contributed nearly 35–40% of global climate displacement in some years.

- Conflict-climate overlap (e.g., drought + civil unrest) in these countries significantly amplifies displacement rates.

The geographical pattern of displacement illustrates that both sudden-onset disasters, such as flooding and cyclones, and slow-onset environmental changes, like desertification and rainfall variability, play a role in uprooting populations. The Lake Chad Basin is a poignant example, where decades of environmental degradation have shrunk water availability, triggered resource-based conflicts, and destabilized agrarian and pastoral livelihoods. Similarly, in arid and semi-arid regions of the Sahel, decreasing land productivity is driving migration into fragile urban centers, placing further stress on overstretched infrastructure and social services.

What emerges from this analysis is a stark reordering of the causes of displacement across the African continent. While conflict remains a significant driver, climate change has overtaken it in many settings as the primary source of involuntary migration. This transition challenges the traditional dichotomy between “climate migrants” and “conflict refugees” and calls for a re-conceptualization of displacement as a multi-causal process where environmental, social, and political drivers intersect. The acceleration of climate displacement, both in scale and speed, demands that policy frameworks, humanitarian responses, and academic research shift accordingly. Without a paradigm shift, current systems will remain reactive, fragmented, and insufficient in the face of one of the century’s most defining humanitarian trends.

Analyzing the case: Empirical Anchors

While aggregate data reveals the alarming rise in climate-induced displacement across Sub-Saharan Africa, granular case studies offer crucial insights into the specific mechanisms through which environmental stress translates into forced mobility. Case studies also allow for contextual analysis of how state capacity, conflict dynamics, livelihood systems, and humanitarian responses interact with climate shocks to influence migration outcomes. The following three examples, Somalia, South Sudan, and Mozambique, were selected for their illustrative value in showcasing diverse types of climate events (drought, flood, cyclone), and varying sociopolitical contexts (fragile states, conflict-affected zones, and coastal regions). These cases collectively illustrate the multi-causal nature of climate displacement and underscore the need for context-sensitive and anticipatory policy responses.

A. Somalia (2021-2023) – Drought, Livelihood collapse, & Urban exodus

Somalia has long been emblematic of complex humanitarian emergencies driven by a combination of state fragility, armed conflict, and climatic volatility. However, the 2021–2023 drought marks a critical turning point in understanding the scale and severity of climate-induced displacement. During this period, Somalia experienced four consecutive failed rainy seasons, leading to the worst drought in over four decades (UNHCR, 2024). In 2022 alone, over 1 million people were internally displaced as rural populations fled desiccated farmlands, dried-up wells, and collapsing pastoral systems (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre [IDMC], 2024).

The displacement process in Somalia illustrates what scholars describe as “anticipatory migration”, movements that occur not in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, but in response to deteriorating environmental conditions that threaten future survival (Black et al., 2011). These patterns were particularly evident in the Bay, Bakool, and Gedo regions, where pastoralists and agro-pastoralists, unable to feed their herds or cultivate crops, moved en masse toward urban centers like Baidoa and Mogadishu. The strain placed on urban infrastructures has been significant, contributing to overcrowding in informal settlements and exacerbating competition over limited aid and employment.

Compounding the climate stress was the weakened governance and continued threat from the al-Shabaab insurgency, which restricted humanitarian access to key drought-affected regions. By 2024, an estimated 4.4 million people were food insecure, and over 43,000 excess deaths, half of them children, were attributed to the drought (AP News, 2025). The Somali case demonstrates the synergistic effect of climate and conflict, and illustrates how slow-onset disasters can have mortality outcomes comparable to conventional armed conflict.

Moreover, Somalia’s displacement crisis challenges the adequacy of existing legal frameworks, which tend to exclude climate-induced migrants from formal refugee protections. As noted by Bettini (2013), the slow, cumulative nature of climate stress does not fit neatly into the “persecution” or “immediate threat” criteria of most international protection regimes. Somalia, therefore, exemplifies the growing need to rethink global displacement categories to accommodate the reality of climate refugees.

B. South Sudan (2024) – Flooding, Loss of territory, & Permanent Displacement

South Sudan, the world’s youngest country, provides a distinct case of climate-induced displacement driven by sudden-onset flooding, compounded by chronic governance deficits and cycles of armed conflict. In 2024, torrential rainfall and overflowing rivers triggered massive floods that displaced over 65,000 people, affecting an additional 735,000 across Jonglei, Unity, and Upper Nile states (Security Council Report, 2024). Unlike episodic flood events of the past, this instance marked the third consecutive year of record flooding, prompting researchers and humanitarian actors to describe the phenomenon as “climate-induced territorial loss” (Kumssa & Jones, 2023).

Unlike drought, which gradually undermines agricultural systems, floods in South Sudan resulted in the immediate destruction of homes, crops, schools, and health facilities, effectively rendering entire villages uninhabitable. Satellite imagery shows large swathes of the Sudd region now permanently submerged. This has forced a redefinition of displacement from temporary crisis management to permanent resettlement, raising complex questions about land rights, cultural heritage, and long-term urban integration.

The flooding crisis in South Sudan also underscores the asymmetry between humanitarian response and environmental recurrence. While agencies such as the World Food Programme (WFP) and UNHCR deployed emergency shelters and food supplies, few investments were made in anticipatory adaptation, such as elevated housing, flood-resistant infrastructure, or early warning systems. As Foresight (2011) notes in its seminal report on climate migration, the lack of planning transforms environmental displacement into a “repeating emergency”, rather than a solvable governance issue.

In South Sudan, displacement also has a gendered dimension. Women, who are primarily responsible for subsistence farming and household water collection, are disproportionately affected by the destruction of local resources and become more vulnerable to exploitation in displacement settings (FAO, 2022). The recurrence of floods without adequate resettlement policies has not only fragmented communities but also eroded social cohesion, undermining post-conflict recovery and stability.

C. Mozambique (2025): Cyclone, Conflict, and Compound Displacement

Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province offers a powerful example of compound displacement, where environmental disaster interacts with political violence to displace already vulnerable populations multiple times. In July 2025, the country experienced one of the most rapid-onset displacement events in its history, when a cyclone-induced flood displaced over 46,000 people in just one week, in tandem with an insurgency attack by Islamist militants (AP News, 2025). This convergence of crises reveals how climate events increasingly function as threat multipliers, exacerbating instability in conflict-affected zones and constraining both mobility and protection.

The case of Mozambique underscores the growing recognition within academic literature that climate cannot be understood as an isolated driver of displacement but must be seen in conjunction with socio-political and economic precarity (Rigaud et al., 2018). In Cabo Delgado, households that had already been displaced by violence in 2020–2021 were again uprooted by flooding, with many being pushed into makeshift camps without access to healthcare, education, or livelihood support.

The humanitarian response has been further challenged by damaged infrastructure, destroyed bridges, and limited access to cyclone-prone areas. Unlike Somalia’s slow-onset, displacement, or South Sudan’s recurrent flooding, Mozambique represents a “cascade displacement” model, where multiple risks overlap to create new categories of vulnerability. This demands a multilayered response that combines climate adaptation, conflict mediation, and long-term resettlement planning. The legal invisibility of climate-displaced persons was evident here, as the government classified affected individuals as “disaster victims” rather than internally displaced persons (IDPs), excluding them from protections under the Kampala Convention. As Schade and Horekens (2022) argue, such administrative misclassifications are common in climate-affected regions and systematically deny rights to populations in need of structured protection.

Together, these three cases reinforce the central thesis of this paper: that climate displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa is not a marginal phenomenon but a structural and multi-dimensional crisis. The forms of displacement vary, slow-onset, sudden-onset, cascading, but the trend is consistent: climate change is not merely a backdrop to displacement; it is now a primary, compounding force. The cases of Somalia, South Sudan, and Mozambique show that future governance frameworks must be sensitive to the interplay of climate with conflict, infrastructure, livelihoods, and legal status if they are to meaningfully address the rising tide of displacement.

Climate as Structure, Not just a shock: Theoretical context

The conceptualization of climate change as a structural force, rather than a series of discrete “shocks”, is critical to advancing scholarly and policy understanding of displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa. Too often, environmental events such as floods, droughts, or cyclones are framed as crises demanding immediate humanitarian intervention. This approach, while useful for mobilizing emergency aid, fails to capture the long-term, cumulative, and systemic nature of climate-related stressors. As Mezzadra and Neilson (2013) have argued in their work on border theory, structural forces shape not only physical movement but also the conditions under which movement becomes a necessity. Applied to climate, this framing demands a reorientation: from viewing climate as an external disruptor to recognizing it as a central axis of governance, inequality, and mobility.

Within this structural lens, climate becomes a determinant of place-based viability, dictating who can remain, who must move, and under what conditions. For instance, prolonged drought is not merely an interruption in rainfall; it represents the slow unraveling of agrarian and pastoralist economies upon which millions depend. Over time, climate degradation erodes the very systems that enable people to live where they are: soil fertility, grazing corridors, freshwater access, and seasonal predictability. When these systems collapse, displacement becomes not a temporary retreat, but a permanent redefinition of habitability (Farbotko & Lazrus, 2012).

This long-view of climate aligns with recent migration scholarship that challenges the “event-response” model prevalent in humanitarian discourse. Black et al. (2011) proposed a typology in which environmental migration is shaped not only by climatic conditions but also by political, economic, and social drivers, making climate a “threat amplifier” rather than a lone trigger. In Sub-Saharan Africa, this amplification is especially potent because of weak state infrastructure, poor adaptation planning, and longstanding developmental deficits. In fragile states like Somalia and South Sudan, even modest climatic shifts can precipitate massive displacements due to the absence of resilience buffers.

The structural nature of climate also extends into the temporal realm. Unlike armed conflict, which is often episodic, climate degradation is gradual and intergenerational. This distinction matters because policy responses remain locked in short-term, reactive cycles. Humanitarian frameworks are designed to address acute crises, not slow-onset phenomena that accumulate over years or decades. As Bettini (2013) has observed, the invisibility of climate-induced suffering in international law stems from its “chronic temporality”—a condition that escapes both the legal imagination and the humanitarian apparatus.

Moreover, climate is increasingly implicated in the production of “new borders”, not just geopolitical, but ecological and socio-economic. Rising temperatures and declining land productivity create implicit boundaries between livable and non-livable zones. These boundaries are often enforced through state policies that limit internal migration, block resettlement, or restrict access to climate-adapted urban areas. Thus, climate-induced displacement becomes not only a result of environmental decline but a political and institutional outcome of how societies manage, or fail to manage, climate risk (Boas et al., 2019).

In this way, the climate–migration nexus must be understood as part of broader systems of mobility governance. For example, in the Lake Chad Basin, desertification has not only reduced water availability but has also increased competition over land and resources, escalating farmer–pastoralist conflict. These disputes have, in turn, triggered retaliatory violence and widespread displacement, often mischaracterized as purely ethno-religious (Rigaud et al., 2018). Here, climate is not a neutral background condition; it is a structuring logic within broader systems of conflict, migration, and resource control.

In sum, the reframing of climate as a structural driver of displacement allows for a more accurate and ethically responsible understanding of mobility in Africa. It moves us beyond simplistic binaries of “climate refugee” vs. “conflict refugee” and acknowledges the entangled and evolving nature of human displacement in a warming world. To address this adequately, both academic scholarship and policy must evolve beyond crisis narratives and toward long-term structural analysis, inter-sectoral planning, and legal innovation.

Pathways of Displacement: From Event to Exodus

Understanding how climate events translate into human displacement requires attention not only to environmental triggers but also to the socio-economic and infrastructural pathways that mediate movement. Climate shocks alone do not produce displacement in a vacuum; they interact with fragile livelihoods, limited state capacity, poor infrastructure, and social vulnerabilities. These intersections form what scholars describe as “pathways of climate-induced displacement”, sequences through which a climate event results in the decision, or necessity, to migrate (Zickgraf, 2018).

One of the most common pathways involves the collapse of agricultural systems due to prolonged drought or erratic rainfall. In regions where rain-fed agriculture is the primary livelihood, such as the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and parts of Central Africa, prolonged dry seasons lead to crop failure, livestock mortality, and declining household income. As a result, families are often forced to engage in rural–urban migration, moving toward secondary towns and informal urban settlements in search of food, water, and alternative income (Gray & Mueller, 2012). This pattern is especially prevalent among youth, who migrate both as a coping strategy and as a form of economic adaptation.

A second, more abrupt pathway is triggered by sudden-onset disasters such as floods, landslides, or cyclones. In these cases, the displacement is involuntary and immediate. Entire communities are forced to flee without preparation as their homes are inundated, roads and schools are washed away, and health facilities are rendered inoperable. For instance, during the 2024 floods in South Sudan, thousands were displaced within hours, with no access to early warning systems or safe evacuation routes (Security Council Report, 2024).

Another significant pathway is driven by chronic food insecurity, often a secondary effect of climate variability. According to UNHCR (2024), over 40 million people in West and Central Africa are currently in food crisis conditions, with climate-linked crop failures exacerbating hunger, malnutrition, and displacement. This leads to what some scholars refer to as “silent displacement”, a gradual erosion of livelihoods that forces individuals to seek stability elsewhere, even though they may not be recognized as IDPs or refugees (Rigaud et al., 2018).

Crucially, these pathways are not mutually exclusive; they often overlap and intensify one another. A household may first experience reduced agricultural productivity (slow-onset), followed by sudden flooding (rapid-onset), and ultimately be displaced by rising food prices or loss of access to health services. The complexity and non-linearity of these pathways challenge policy systems that rely on discrete categories of disaster or displacement.

Policy and Governance Gaps

Despite growing recognition of the climate–displacement nexus in academic and humanitarian discourse, governance frameworks remain inadequate, fragmented, and reactive. Most displacement policies in Sub-Saharan Africa continue to be rooted in the post-World War II refugee regime, which centers on conflict persecution and cross-border movement. Climate-induced internal displacement, especially when gradual or repetitive, often falls outside existing legal protections (Ferris, 2020). As a result, millions are displaced without access to durable solutions or formal recognition.

One key governance gap lies in the legal invisibility of climate-displaced persons. The 1951 Refugee Convention does not recognize environmental causes as grounds for protection, and although the African Union’s Kampala Convention (2009) offers a more expansive definition of internal displacement, it lacks enforcement mechanisms and is inconsistently applied across countries. Consequently, those displaced by climate events are often categorized as “disaster victims” rather than IDPs, rendering them ineligible for targeted humanitarian aid or resettlement assistance (Schade & Horekens, 2022).

In terms of operational response, there is a persistent disconnect between climate adaptation policy and displacement governance. Climate strategies often prioritize carbon mitigation or macro-level resilience, while displacement policies remain locked in short-term emergency response. This lack of integration is evident in the low investment in forecast-based financing, early warning systems, and anticipatory infrastructure such as elevated housing or flood buffers (Boas et al., 2019). Moreover, host communities receiving large influxes of displaced populations are rarely supported with scaled-up education, healthcare, and housing infrastructure, creating localized crises and increasing the risk of conflict.

The international donor architecture also contributes to governance paralysis. Funding for climate resilience tends to be siloed from humanitarian relief, and multi-year investments in adaptation are often overlooked in favor of short-term crisis mitigation. This bifurcation results in a recurring cycle of unpreparedness, as the same regions suffer year after year without meaningful progress toward long-term solutions.

Finally, migration control policies in Europe and North Africa have inadvertently exacerbated governance failures. Externalization strategies, such as border militarization, return agreements, and offshoring asylum processes, focus on containment rather than protection. These policies fail to address the root environmental causes of displacement and often criminalize migration that is, in fact, an adaptive response to climate vulnerability (Amnesty International, 2018).

Policy Recommendations

Addressing the scale and complexity of climate-induced displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa demands a fundamental shift in policy thinking, from reactive crisis response to anticipatory governance, structural reform, and human-centered adaptation. The following recommendations are not prescriptive blueprints, but foundational pillars for building a more coherent and just response to the multifaceted realities of climate displacement across the continent.

First, there is an urgent need to expand legal and institutional recognition of climate-induced displacement. Current international protection frameworks, most notably the 1951 Refugee Convention, exclude those fleeing slow-onset climate disasters from formal refugee status. While the African Union’s Kampala Convention (2009) offers broader protection for internally displaced persons, it remains inconsistently enforced and often fails to name climate explicitly as a cause. National legal systems must be reformed to explicitly incorporate slow- and rapid-onset environmental changes as legitimate grounds for displacement status. This includes recognizing climate-displaced persons within IDP policies, enabling access to humanitarian protection, basic services, and durable solutions. Legal recognition is not a symbolic gesture; it is the precondition for meaningful intervention, resource mobilization, and long-term integration.

Second, displacement and climate adaptation planning must be integrated at all levels of governance. Too often, displacement is treated as an aftershock rather than an embedded risk within national climate policies. National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and disaster risk reduction strategies should explicitly address population mobility as a form of adaptation, incorporating displacement forecasts into environmental planning and urban development. Infrastructure in high-risk areas, particularly housing, water systems, transportation corridors, and healthcare, must be upgraded or reimagined to withstand recurring climate hazards. Simultaneously, resettlement plans for vulnerable communities should be developed preemptively, based on climate vulnerability assessments, rather than triggered after displacement has already occurred. This shift toward anticipatory governance would allow governments and humanitarian actors to reduce harm, increase resilience, and build sustainable systems of protection.

Third, migration should be framed and supported as a proactive form of resilience, rather than as a sign of failure. For decades, development and security discourses have pathologized migration, viewing it as something to be prevented, contained, or reversed. Yet, in many African contexts, mobility is not only a coping strategy but also a rational, adaptive response to unviable environmental conditions. Policies that facilitate safe, dignified, and voluntary migration, including circular mobility schemes, inter-regional labor agreements, and climate-resilient housing incentives, should be encouraged. Governments must move away from punitive or restrictive migration controls and instead create legal pathways for relocation, whether internal or cross-border, especially for populations living in climate “hotspots” with declining viability.

Fourth, there must be a concerted investment in host community infrastructure and inclusion strategies. As displaced populations move toward urban peripheries or safer ecological zones, host communities are often overwhelmed, resulting in tensions over land, resources, and service provision. Policymakers should ensure that incoming displaced populations do not displace residents from existing services. Investment in host regions must be commensurate with the scale of movement, including the expansion of public education, healthcare, water access, and housing projects. Moreover, social cohesion programs, such as local integration committees, community-driven planning, and equitable livelihood support, are essential to prevent resentment, conflict, and the formation of parallel informal settlements.

Fifth, community-based and locally led resilience initiatives must be prioritized over top-down technocratic interventions. International organizations and donors have a tendency to impose standardized solutions without accounting for cultural, ecological, or institutional specificity. Instead, funding should be directed toward grassroots adaptation strategies already being implemented in rural African contexts, such as community water harvesting systems, drought-resistant seed cooperatives, solar-powered irrigation, traditional land rotation systems, and village-level early warning mechanisms. These approaches build on existing knowledge, require less infrastructure, and ensure greater ownership by the communities most affected by climate stress.

Finally, a major governance challenge lies in the siloed nature of climate and humanitarian financing. Funding streams are currently divided between reactive emergency responses and long-term climate adaptation, resulting in underinvestment in anticipatory measures. This fragmentation must be addressed by establishing flexible, multi-year funding mechanisms that span both domains. International donors, including the Green Climate Fund, bilateral aid agencies, and multilateral institutions, should support cross-sector programs that target vulnerable communities through resilience building, ecosystem restoration, social protection, and displacement prevention. Forecast-based financing models that pre-position aid before disasters strike should be scaled up, particularly in flood-prone and drought-affected regions.

In sum, policy responses to climate-induced displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa must break from their crisis-centered, fragmented foundations and embrace an approach grounded in anticipation, equity, and mobility justice. The structural nature of climate vulnerability demands structural solutions, not just emergency relief. This will require courage from policymakers, flexibility from donors, innovation from humanitarian agencies, and leadership from affected communities themselves.

Conclusion

Climate change is no longer an emerging challenge for African mobility systems; it is the defining context of displacement in the 21st century. The cases of Somalia, South Sudan, and Mozambique reveal that climate is not simply a trigger of temporary crisis but a structural condition that reshapes entire geographies of human habitation and migration. The sheer scale and speed of climate-induced displacement demand an urgent rethinking of governance, law, and humanitarian action.

If policies remain reactive, narrowly legalistic, and siloed between climate and migration sectors, millions will continue to face repeated, protracted, and invisible displacement. The current frameworks, rooted in the Cold War logic of persecution and war, are unfit for a world of collapsing ecosystems, disappearing arable land, and vanishing livelihoods.

The future of migration governance in Africa must pivot toward anticipation, resilience, and justice. Legal protections must evolve to match lived realities. Humanitarian aid must shift from emergency response to long-term adaptation. Most importantly, climate must be seen not as an external shock, but as a governing force, a boundary, a displacer, and a determiner of life trajectories.

Credit to the following Reference List

This piece of writing has been written using the following scholarly and institutional sources, each of which contributed to its conceptual framework, empirical evidence, or policy analysis:

Mezzadra, S., & Neilson, B. (2013).

Border as method, or the multiplication of labor. Duke University Press.

→ Provided the theoretical foundation for conceptualizing climate as a structural force that governs mobility and boundaries beyond territorial lines.

Bettini, G. (2013).

Climate barbarians at the gate? A critique of apocalyptic narratives on “climate refugees”. Geoforum, 45, 63–72.

→ Informed the critique of alarmist climate narratives and helped frame climate-induced displacement as a structural and legal blind spot.

Black, R., Bennett, S. R., Thomas, S. M., & Beddington, J. R. (2011).

Migration as adaptation. Nature, 478(7370), 447–449.

→ Contributed to the argument that migration is a legitimate and adaptive strategy in the face of environmental stressors.

Farbotko, C., & Lazrus, H. (2012).

The first climate refugees? Contesting global narratives of climate change in Tuvalu. Global Environmental Change, 22(2), 382–390.

→ Supported the paper’s argument about the political invisibility and complexity of slow-onset climate displacement.

Boas, I., Farbotko, C., Adams, H., Sterly, H., Bush, S., van der Geest, K., … & Wiegel, H. (2019).

Climate migration myths. Nature Climate Change, 9(12), 901–903.

→ Informed the discussion of migration governance myths and offered evidence for designing mobility as part of climate adaptation.

Zickgraf, C. (2018).

Immobility in the context of environmental stressors. In McLeman & Gemenne (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Environmental Displacement and Migration.

→ Helped to frame displacement as part of complex decision-making chains and broadened the notion of forced immobility.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. (2024).

Global Report on Internal Displacement.

→ Served as the primary source for displacement data trends, including annual figures for climate-related displacement in Africa.

UNHCR. (2024).

Strategic Directions 2024–2030.

→ Informed the policy analysis of current institutional approaches and gaps in addressing climate-displaced populations.

Security Council Report. (2024).

Climate and Security in the Horn of Africa.

→ Provided specific regional case data, especially for Somalia, South Sudan, and the Sahel zone.

Reuters. (2023).

Africa sees sixfold rise in climate-driven displacement. https://www.reuters.com/

→ Offered recent statistical data and highlighted the alarming growth rate of climate-related internal displacement.

AP News. (2025).

UNHCR warns of rising displacement amid funding cuts. https://www.apnews.com/

→ Provided figures and qualitative insights into humanitarian response shortfalls across climate-affected African countries.

Amnesty International. (2018).

Human rights violations in Niger’s migration control.https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr43/0010/2018/en/

→ Offered a critical perspective on the securitization of African migration routes and European externalization practices.

Rigaud, K. K., de Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Bergmann, J., Clement, V., Ober, K., … & Midgley, A. (2018).

Groundswell: Preparing for internal climate migration. World Bank Group.

→ Provided scenario-based forecasting on internal migration patterns under different climate trajectories, used to support anticipatory planning arguments.

Ferris, E. (2020).

The politics of climate-induced migration. Brookings Institution.

→ Offered critical insights into the political resistance to recognizing climate-induced migration in international law.

Gray, C. L., & Mueller, V. (2012).

Drought and population mobility in rural Ethiopia. World Development, 40(1), 134–145.

→ Contributed case-based evidence for rural-to-urban migration pathways driven by agricultural collapse and water scarcity.

World Bank. (2021).

Climate risk and adaptation in African agriculture: Assessment and recommendations.

→ Provided recommendations on climate-resilient infrastructure and agricultural adaptation strategies discussed in policy solutions.

Schade, J., & Horekens, J. (2022).

Legal voids in climate displacement: Between disaster response and rights protection. International Review of the Red Cross.

→ Supported the legal analysis of why climate-displaced populations remain outside most protection regimes and policy frameworks.