The Sahel, a semi-arid belt stretching across Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Mauritania, has emerged as one of the most fragile regions on the planet. The area is gripped by overlapping crises: jihadist insurgencies, mass displacement, hunger, droughts, climate degradation, and political instability marked by successive coups. In response, international donors, notably France in particular, the European Union (EU), the United States (US), and Canada, have expanded aid, military operations, and development programs in the region. Framed under humanitarian narratives, these actions are increasingly being critiqued for masking deeper geopolitical motives.

This article interrogates the extent to which foreign assistance in the Sahel is driven by genuine humanitarian concern versus geopolitical interests such as migration containment, counterterrorism, resource security, and reputational control. Through a comparative analysis of key donor behaviors and grounded case studies in Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso, the article argues that donor engagement in the Sahel is more strategically calculated than altruistically motivated. Applying critical humanitarianism and realist international relations theory, the piece reveals how fear of spillover, terrorism, irregular migration, and influence loss continue to shape aid flows and foreign presence in the region.

Prologue

The Sahel region stands today as one of the most geo-strategically charged and socio-politically volatile areas in the world. Stretching across the southern edge of the Sahara Desert, this fragile belt has become a flashpoint where insecurity, governance crises, environmental stress, and humanitarian need converge. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA, 2025), over 34 million people in the region are in need of assistance, while more than 6 million have been forcibly displaced by conflict and climate-induced disasters. The region is at once a humanitarian emergency zone and a strategic chessboard for international actors.

In recent years, the Sahel has witnessed a dangerous escalation of instability. Between 2021 and 2023 alone, three military coups toppled civilian governments in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. In parallel, the UN’s MINUSMA peacekeeping mission began a phase-out in Mali, while French and European troops were expelled amid rising anti-colonial rhetoric and popular discontent. Into this vacuum stepped Russia’s Wagner Group, further complicating the geopolitical calculus. As insurgent groups linked to al-Qaeda and Islamic State continue to expand their operations, donor States are faced with a dilemma: withdraw and risk chaos, or remain engaged through aid and influence at the cost of local legitimacy.

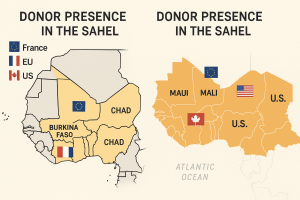

Against this backdrop, donor engagement in the Sahel has intensified. France and the EU have historically played leading roles through military interventions like Operation Barkhane and the EUCAP Sahel mission, as well as development investments via the EU Trust Fund for Africa. The United States has quietly maintained a robust counterterrorism presence under AFRICOM, with a sprawling drone base in Niger. Meanwhile, Canada has focused on development diplomacy, gender programming, and peacekeeping contributions. Yet despite billions in aid and military assistance, violence continues to surge, governance weakens, and local populations grow increasingly distrustful of foreign involvement.

This raises an urgent ethical and political question: are donor actions in the Sahel truly motivated by humanitarian compassion, or do they reflect deeper strategic calculations? This analytical piece critically interrogates the motivations behind Western donor engagement in the region, guided by the central research question: To what extent are international aid efforts in the Sahel driven by humanitarian concerns versus geopolitical interests of Actor-States like the EU, US, and Canada?

The analysis that follows will combine theoretical frameworks (1) critical humanitarianism, (2) realism, and (3) postcolonial critique, with empirical case studies and policy analysis. By unpacking how aid is mobilized, framed, and operationalized in the Sahel, this piece seeks to move beyond surface-level narratives of “stabilization” and “resilience” to examine the underlying logics of control, containment, and competition. The stakes are high; not only for the Sahel’s future but for how we understand the politics of international aid more broadly.

The Sahel represents a convergence point of chronic vulnerability and international strategic interest. It is a region that continues to experience acute humanitarian suffering alongside intensifying foreign intervention. According to the UN OCHA (2025), 34.5 million people in the central Sahel require humanitarian assistance, marking a 62% increase since 2019. In Burkina Faso alone, the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) surged from 87,000 in 2018 to over 2.1 million in 2025, making it one of the fastest-growing displacement crises globally. Across Mali, Niger, and Chad, millions lack access to healthcare, clean water, and education due to escalating insecurity.

Armed groups affiliated with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) have expanded operations since 2017, particularly in the tri-border area (Liptako-Gourma). In 2024, ACLED reported 7,364 violent incidents across the Sahel, with Burkina Faso accounting for nearly half. These attacks disproportionately affect rural populations, aid workers, and local administrators, weakening state legitimacy and obstructing humanitarian access.

Food insecurity has reached alarming levels. The World Food Programme (2025) estimates that over 18 million people face acute food shortages, a consequence of climate volatility, inflation, and disrupted agricultural production. Niger and Chad are among the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries, with rising temperatures, desertification, and unpredictable rainfall pushing thousands into migratory movement each year.

Democratically, the region has suffered dramatic backsliding. Mali (2020 & 2021), Chad (2021), Burkina Faso (2022), and Niger (2023) all experienced military coups. These power transitions were accompanied by mass protests both for and against foreign military presence, particularly France’s, culminating in the withdrawal of French troops from Mali (2022) and Burkina Faso (2023), and EUCAP operations being significantly reduced in Niger by 2024. The UN’s MINUSMA mission, once hailed as a stabilizing force in Mali, began a full drawdown in 2023 following demands from the transitional government.

At the same time, Russia’s Wagner Group has made visible inroads, establishing security arrangements with Mali and allegedly with elements in Niger, offering military services in exchange for resource concessions. This new foreign presence has triggered a recalibration among Western donors concerned about losing influence to non-democratic powers.

Donor fatigue and shifting global priorities (including the Ukraine war and Gaza crisis) have contributed to reduced aid flows. The UNHCR and IOM report underfunding levels of over 60% for Sahelian humanitarian response plans in 2024. This erosion of international support comes as civilian populations express growing frustration toward both their governments and foreign actors, whom they perceive as ineffective or self-interested.

The multiplicity of crises has fostered an environment of hybrid insecurity: jihadist violence, criminal networks, intercommunal conflict, and elite power struggles coexist, rendering one-size-fits-all approaches to aid and peacebuilding increasingly ineffective.

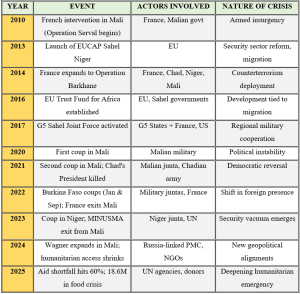

Table 1: Key Events in the Sahel Crisis Landscape (2010-2025)

In sum, the Sahel crisis is not simply humanitarian in nature but deeply entangled with issues of governance collapse, ecological stress, militarization, and foreign policy agendas. International interventions have often responded in fragmented and interest-driven ways. The region increasingly reflects not a zone of international rescue but a battleground of contested sovereignties, where donor priorities, local agency, and geopolitical rivalry converge.

Theorizing the situation

Understanding the motivations behind donor actions in the Sahel requires a multidisciplinary theoretical approach that interrogates both normative claims and realpolitik strategies. This section employs three interlocking theoretical lenses: (1)Critical Humanitarianism, (2)Realist International Relations Theory, and (3)Postcolonial Theory, to reveal how donor practices in the Sahel are shaped not merely by needs on the ground, but by fears of insecurity, loss of influence, and reputational stakes in global governance.

- Critical Humanitarianism

Critical Humanitarianism challenges the assumption that aid is apolitical or purely altruistic. Drawing on thinkers such as Didier Fassin (2012) and Miriam Ticktin (2011), this perspective argues that humanitarianism is often infused with bio-political logics, wherein some lives are made grievable while others are instrumentalized for policy goals. In the Sahel, humanitarian rhetoric is frequently used to justify interventions that serve dual purposes, saving lives while stabilizing spaces deemed dangerous to Western interests. The framing of the Sahel as a zone of “exceptional crisis” allows donors to bypass local sovereignty and assert emergency governance, often without sustained local consultation.

For instance, the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, ostensibly created to “address root causes of migration,” has largely financed border surveillance, return operations, and local security forces, illustrating how humanitarian logic becomes enmeshed with containment agendas. Critical humanitarianism thus reveals how compassion and control operate in tandem.

- Realist International Relations Theory

From a realist standpoint, international aid and security policy are extensions of national interest. States intervene not out of moral obligation but to secure influence, deter threats, and protect strategic assets. Applied to the Sahel, realism explains why the United States maintains drone bases in Niger despite minimal public development programming, or why France has historically projected power in West Africa through a “France-Afrique” military-development nexus.

Realist theory accounts for the persistence of engagement even amid democratic reversals. For example, France continued supporting Sahelian militaries after successive coups, prioritizing counterterrorism cooperation over normative commitments to democratic governance. Similarly, the U.S. supports AFRICOM intelligence operations in the Sahel with minimal scrutiny of local human rights abuses, driven by broader fears of extremist spillover and great power competition, particularly with Russia and China.

- Postcolonial Theory

Postcolonial theory offers a structural critique of how donor-recipient relations are embedded in historical hierarchies of power and race. Scholars like Achille Mbembe and Frantz Fanon emphasize that development and aid are often deployed through a colonial lens, where Africa becomes the passive recipient of “solutions” crafted elsewhere. In the Sahel, donor language about “capacity-building” and “resilience” frequently masks a deeper pattern of epistemic dominance, wherein Western norms, strategies, and definitions of stability are privileged over local knowledge and political will.

This is particularly evident in migration policy: EU programs in Niger funded under development frameworks have forcibly reshaped local economies around border control and anti-smuggling patrols, often leading to local displacement and economic precarity. The paradox is stark—Europe frames itself as a humanitarian actor while enforcing externalized borders in Africa, echoing colonial logics of extraction and discipline.

Synthesis

These frameworks collectively underscore that donor actions in the Sahel cannot be reduced to binary categories of “help” or “harm.” Instead, they reflect hybrid motives shaped by strategic fear, moral legitimation, and postcolonial path dependencies. By applying these theoretical tools, this article interrogates not only what donors do, but also why and how they justify it, and whose interests are truly served in the process. The next sections will apply these frameworks in comparative and empirical analyses of France, the EU, the US, and Canada to further dissect the intersection between humanitarian discourse and geopolitical strategy in the Sahel.

Donor Motives & Behavior – Comparative Analysis

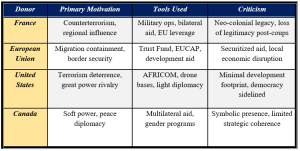

In this section, we examine the behavior of key donors, France, the European Union, the United States, and Canada, in the Sahel. Drawing on the theoretical framework previously outlined, we highlight how each donor’s actions are influenced by a mixture of humanitarian justification and geostrategic imperatives. The analysis is based on official donor strategy documents, aid flow datasets, military operations, and recent political developments in Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and the wider Sahel region.

A. France & the EU

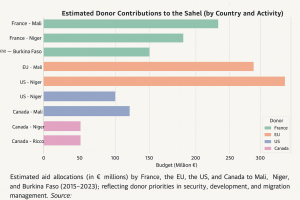

France’s presence in the Sahel is rooted in its colonial legacy and strategic interest in Francophone Africa. Through Operation Barkhane (2014–2022), France stationed approximately 5,100 troops across the region, aiming to contain jihadist groups and stabilize Sahelian governments. Despite the operation’s stated humanitarian and peacekeeping objectives, critics argue that it entrenched authoritarian regimes and failed to address the root causes of instability. Following military coups and rising anti-French sentiment, Barkhane was officially terminated in 2022, but French influence persists via bilateral defense agreements and EU-coordinated missions.

The EU, through the EUCAP Sahel missions and the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF), has focused on border control, migration management, and security sector reform. Between 2016 and 2021, the EU disbursed over €4.7 billion to the Sahel region, with Niger emerging as a strategic partner due to its cooperation in stemming migration flows. Much of this funding was directed not toward humanitarian relief, but to programs that strengthen local police and border forces, illustrating the securitized logic of European aid. For example, in Agadez (Niger), former smuggling economies were dismantled under EU pressure without viable alternatives, exacerbating local unemployment and resentment.

B. The United States of America

The United States has approached the Sahel primarily through a counterterrorism lens. The U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) has established forward-operating bases in Niger, including the $110 million drone base in Agadez (Niger Air Base 201). These facilities support ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance) missions and occasional airstrikes targeting jihadist factions in the region.

Despite the heavy military footprint, U.S. development aid has remained modest. USAID’s focus in the Sahel is often couched in resilience and food security, but much of it aligns with stability operations or is implemented through multilateral partners to avoid entanglement. This reflects a preference for “light-footprint diplomacy”, leveraging intelligence and military support while avoiding the complexities of State-building. According to a 2023 Congressional Research Service report, U.S. engagement in the Sahel is increasingly driven by concerns over Russian influence, especially after Wagner Group deployments in Mali and Burkina Faso.

Washington’s policy has also emphasized regime stability over democratic governance. After the 2023 coup in Niger, U.S. condemnation was cautious and limited. This silence reflects geopolitical pragmatism: maintaining drone operations and intelligence partnerships has outweighed normative commitments to constitutional order.

C. Canada

Canada’s role in the Sahel is more subdued but symbolically significant. It emphasizes “feminist international assistance,” peacekeeping, and development through multilateral channels such as the UN, World Bank, and African Union. From 2016 to 2023, Canada allocated approximately CAD 620 million to the Sahel, focusing on gender equality, education, climate resilience, and conflict prevention.

Unlike France or the U.S., Canada has avoided direct military entanglement. However, its contributions are often perceived as geopolitical signaling, an effort to maintain relevance in Francophone Africa and display a values-based foreign policy. For example, Canada deployed 250 troops and helicopters to MINUSMA between 2018 and 2019, a short-lived mission that ended amid concerns about the deteriorating security situation and uncertain political mandate.

Canadian officials have also used Sahel engagement to amplify global development branding. Yet critics argue that Canada’s aid has been inconsistently applied and often lacks a long-term strategy rooted in local realities. Furthermore, as Global Affairs Canada’s evaluations acknowledge, many programs in the region face barriers due to insecurity, limited state capacity, and weak coordination among donors.

Comparative Summary

Together, these donors represent a complex ecosystem of interests in the Sahel. While humanitarian discourse persists, aid flows and diplomatic behavior are deeply influenced by migration pressures, regional rivalries, and fears of instability spilling into Europe and beyond. Their actions, whether militarized, securitized, or symbolic, have significant implications for sovereignty, legitimacy, and the lived experiences of Sahelian communities.

Case Studies: Local Realities vs. Donor Narratives

To critically assess the gap between donor rhetoric and on-the-ground realities, we examine three key country cases: Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. These case studies illustrate how donor interventions, although framed as humanitarian or development-oriented, often exacerbate local fragility, reinforce elite interests, and ignore structural conditions that drive violence and displacement.

- Niger: Border Security at the Expense of Communities

Niger has emerged as a linchpin in EU migration policy. Through the EU Trust Fund for Africa, Niger received over €1 billion between 2016 and 2022, a significant share of which was dedicated to border policing, anti-smuggling patrols, and migration management infrastructure. In Agadez, where cross-Saharan mobility was historically part of the local economy, EU-funded crackdowns led to the criminalization of traditional livelihoods.

Research by Amnesty International (2018), Mixed Migration Centre (2021), and Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (2021) shows that these policies pushed migration underground, increased extortion and corruption, and disproportionately harmed poor communities. Transporters, hotel workers, and small traders, once part of a legal migration economy, lost their income due to new legal frameworks. Smuggling has not stopped; rather, it has become more dangerous and predatory.

Despite being framed as “resilience-building,” these interventions have resulted in economic precarity, human rights abuses, and a profound legitimacy crisis for both local and foreign authorities. Niger’s authorities, often acting under EU pressure, passed laws such as Law 2015-036 that were inconsistently applied and vaguely defined, leading to legal uncertainty and further alienation of local populations. This case underscores how European geopolitical fears, particularly of African migration, can override both local development and governance needs.

- Mali: From Counter-terrorism to Geopolitical Realignment

Mali has been a theater for military-led stabilization since France’s Operation Serval (2013) and later Barkhane (2014–2022). Although France framed its military presence as protecting civilians from jihadist violence, local perceptions often characterized it as a neo-imperial occupation. According to Afrobarometer (2021), a majority of Malians believed foreign troops were more interested in their national interests than in local peace. An International Crisis Group (2022) briefing confirmed that French counterterrorism approaches often sidelined political dialogue and reconciliation efforts in favor of kinetic military action.

Following successive coups in 2020 and 2021, Mali’s transitional authorities pivoted toward Russia’s Wagner Group, expelling French forces and the UN’s MINUSMA. Wagner’s deployment, under the guise of state security assistance, has been linked to serious abuses, including the 2022 Moura massacre, where over 300 civilians were reportedly killed, according to Human Rights Watch (2022). While framed as restoring sovereignty, Wagner’s presence also serves as a signal of Mali’s defiance against Western influence and a reshaping of regional alliances.

Meanwhile, humanitarian needs have escalated: over 1 million people remain displaced, and 42% of the population faces food insecurity (OCHA, 2024). The withdrawal of MINUSMA and the exodus of key NGOs, citing security concerns and government restrictions, have left many areas underserved. Analysts have warned that the vacuum created by donor withdrawal is being filled not by effective governance, but by militias, hybrid actors, and predatory security networks. The Malian case thus illustrates how shifts in geopolitical alignment can disrupt humanitarian access and worsen civilian vulnerability.

- Burkina Faso: Rejection of External Influence and the Rise of Militant Control

Burkina Faso has experienced a dramatic deterioration in security, with jihadist groups now controlling over 40% of the country’s territory. In 2024 alone, ACLED reported 3,529 violent incidents, including mass killings, village burnings, and IED attacks. Despite substantial international aid, including from France, the EU, and Canada, government legitimacy has weakened, and the military junta has increasingly distanced itself from traditional Western donors.

The junta that seized power in 2022 framed its legitimacy around anti-colonial rhetoric and national sovereignty. Following the expulsion of French troops in early 2023, the government turned to alternative partners, including Turkey, Russia, and other non-Western actors. Military cooperation agreements have been signed with Moscow, and there is growing evidence of increased paramilitary assistance. Meanwhile, Western aid actors have faced restricted access, media hostility, and deteriorating coordination.

Yet humanitarian needs have surged: over 2.1 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), school closures affecting nearly 1 million children, and near-total aid exclusion from conflict zones (UNHCR, 2025; Save the Children, 2024). Humanitarian corridors are increasingly rare due to militant control and an administrative vacuum in peripheral regions. Burkinabè civil society groups have criticized both the past failures of Western donors and the current militarized approaches.

Synthesis

These case studies reveal a persistent contradiction: donors claim to promote security, development, and resilience, yet their interventions often amplify exclusion, militarization, and dependency. While donor narratives foreground strategic partnerships and technical solutions, local populations experience heightened vulnerability and shrinking civic space.

Aid is thus not neutral; it reflects and reproduces global hierarchies. The divergence between intention and outcome raises fundamental questions about accountability, legitimacy, and the future of cooperation in the Sahel. These tensions are further examined in the next section.

Critical Analysis & Discussion

This analysis reveals a persistent contradiction between donor discourse and actual outcomes in the Sahel. On paper, foreign interventions are framed around development, stability, and humanitarian assistance. Yet in practice, they often produce militarized landscapes, conditional aid systems, and externally imposed governance models. These dynamics raise several analytical questions.

- Exporting Security, Importing Dependence?

One of the central dilemmas is whether foreign donors are exporting genuine security or inadvertently creating long-term dependency. Military assistance has overshadowed institution-building, with counterterrorism taking precedence over social cohesion. The proliferation of drone bases, surveillance networks, and elite force training programs has not translated into safer lives for civilians. Instead, it has created dual States, one secure for elites and donors, and another vulnerable for ordinary people.

Moreover, aid conditionalities tied to border control, political compliance, or migration deterrence reduce local ownership of development agendas. The Sahelian states remain dependent not only on foreign funds but also on donor-defined narratives of what constitutes progress or risk. This undermines sovereignty and civic participation.

- Aid as a tool of Political Agenda

The evidence also suggests that donors use aid to secure diplomatic or reputational goals. The EU’s migration deals with Niger, France’s defense pacts with ex-colonies, and the U.S. focus on containing Russian influence illustrate how humanitarian logic becomes secondary to foreign policy calculus. Aid is instrumentalized to achieve strategic ends, not merely to alleviate suffering.

At the same time, donors are not monolithic. Canada’s soft power approach and multilateralism contrast with the militarized strategies of France and the U.S. Yet even these distinctions blur when all actors operate within the same postcolonial framework of North-South asymmetry and securitized governance.

- African Agency consequences

The dominance of external actors has crowded out African agency. Civil society voices, traditional leaders, and grassroots movements are rarely consulted in program design or security operations. This results in interventions that are technically sophisticated but socially tone-deaf. Furthermore, Sahelian regimes have learned to manipulate donor logic, projecting cooperation while centralizing power, sidelining dissent, and circumventing democratic accountability. As coups proliferate, Western donors are left choosing between complicity and irrelevance, often opting for short-term stability at the expense of long-term reform.

- Toward a new model of cooperation

A new model must go beyond slogans of partnership and embrace co-creation, power-sharing, and locally rooted legitimacy. It should prioritize trust-building, context-specific learning, and equitable decision-making. Security cannot be outsourced, nor can resilience be imported.

Conclusion & Policy Recommendations

This piece has argued that donor engagement in the Sahel is largely shaped by geopolitical and strategic motives, even when framed as humanitarianism. France, the EU, the United States, and Canada each present different narratives, but they converge in reinforcing patterns of securitization, conditionality, and elite-centric governance. Rather than enabling sustainable peace or resilience, current donor strategies risk reproducing dependency, eroding sovereignty, and fostering backlash among local populations. The humanitarian language used often masks more coercive objectives, border fortification, influence preservation, and reputational management.

Foreign aid in the Sahel must evolve from its current securitized and paternalistic orientation toward one rooted in African agency and long-term transformation. To support African-led peacebuilding, international actors should prioritize conflict resolution frameworks designed and led by local communities themselves, whether through traditional leaders, youth-led movements, or regional mechanisms like ECOWAS and the African Union. The success of any peace process depends on legitimacy, which cannot be imposed externally but must emerge from within. Similarly, aid conditionalities must be overhauled. It is unacceptable for life-saving assistance to be tethered to migration control quotas or regime loyalty. Donor policies should be guided by transparent, needs-based assessments grounded in international humanitarian law, rather than diplomatic favoritism or short-term strategic bargains. In a context where coups and transitions are frequent, donors must avoid the temptation to reward superficial stability over democratic or popular legitimacy.

Development itself must be de-securitized. Too often, investment flows into border police, surveillance equipment, and military training while healthcare systems collapse and schools close. True resilience, social, economic, and ecological, emerges not from drones and checkpoints but from educated youth, functioning institutions, and climate-adapted livelihoods. This transformation also requires participatory mechanisms. Aid must be reimagined as a horizontal partnership, not a vertical transaction. Programs should be co-designed with the people they intend to serve, including women’s associations, displaced communities, and civil society watchdogs. This includes ensuring that decision-making bodies are not just inclusive on paper, but empowered in practice.

Accountability must be central to any future cooperation. External interventions, military or civilian, should be subject to independent oversight, with grievance mechanisms accessible to ordinary citizens. Sahelian communities have long suffered in silence; international partners must now listen with humility and act with responsibility. Finally, the very narrative of “helping Africa” must be challenged. It often rests on colonial hierarchies and paternalistic assumptions. Instead, donors must recognize and affirm the Sahel’s own political imagination, survival strategies, and democratic aspirations. Only by transforming the language, logic, and architecture of aid can we begin to reverse the cycle of dependency and move toward a more just and reciprocal global order.

By challenging the status quo, these reforms can help donors avoid perpetuating the very crises they seek to resolve and offer a more ethical, effective path forward in one of the world’s most fragile regions.